Arthur Brooks is a best-selling author, a man of clear intellect, solid decency, and enough charm to disarm even a hardened cynic. I read one of his books, From Strength to Strength, which tackles the subject of happiness with insight, elegance, and more than a few glimmers of genuine wisdom. For a week or so, I even took his ideas seriously—pondering the slow fade of professional relevance, the shift from fluid to crystallized intelligence, and the noble art of growing old with grace.

And then I moved on with my life.

What I didn’t move on from, unfortunately, was the onslaught of Brooks’ happiness essays in The Atlantic. They appear like clockwork, regular as a multivitamin—each one another serving of cod liver oil ladled out with the same hopeful insistence: “Here, take this. It’s good for you.” The problem isn’t Arthur Brooks. It’s happiness itself. Or rather, happiness writing—that genre of glossy, over-smoothed, well-meaning counsel that now repels me like a therapy dog that won’t stop licking your face during a panic attack.

Let me try to explain why.

1. The Word “Happiness” Is Emotionally Bankrupt

The term happiness is dead on arrival. It lands with the emotional resonance of a helium balloon tied to a mailbox. It evokes cotton candy, county fairs, and the faded joy of children playing cowboys and Indians—an aesthetic trapped in amber. It feels unserious, childish even. I can’t engage with it as a concept because it doesn’t belong in the adult vocabulary of meaning-making. It’s not that I reject the state of being happy—I’m just allergic to calling it that.

2. It Feels Like Cod Liver Oil for the Soul

Brooks’ essays show up with the regularity and charm of a concerned mother armed with a spoonful of something you didn’t ask for. I click through The Atlantic and there it is again: another gentle lecture on how to optimize my inner light. It’s no longer nourishment. It’s over-parenting via prose.

3. Optimizing Happiness Is a Ridiculous Fantasy

Some of Brooks’ formulas for increasing happiness start to feel like they were dreamed up by a retired actuary trying to convert existential dread into a spreadsheet. As if flourishing could be reduced to inputs and outputs. As if there’s a number on the dial you can crank up if you just follow the steps. It’s wellness-by-algorithm, joy-by-numbers. I’m not a stock portfolio. I’m a human being. And happiness doesn’t wear a Fitbit.

4. Satire Has Already Broken the Spell

Anthony Lane, in his New Yorker essay “Can Happiness Be Taught?,”

dismantled this whole genre with surgical wit. Once you’ve read a masterful takedown of this kind of earnest life-coaching prose, it’s impossible to take it seriously again. Like seeing the zipper on a mascot costume, the magic disappears. You’re just watching a grown-up in a plush suit tell you to breathe and smile more.

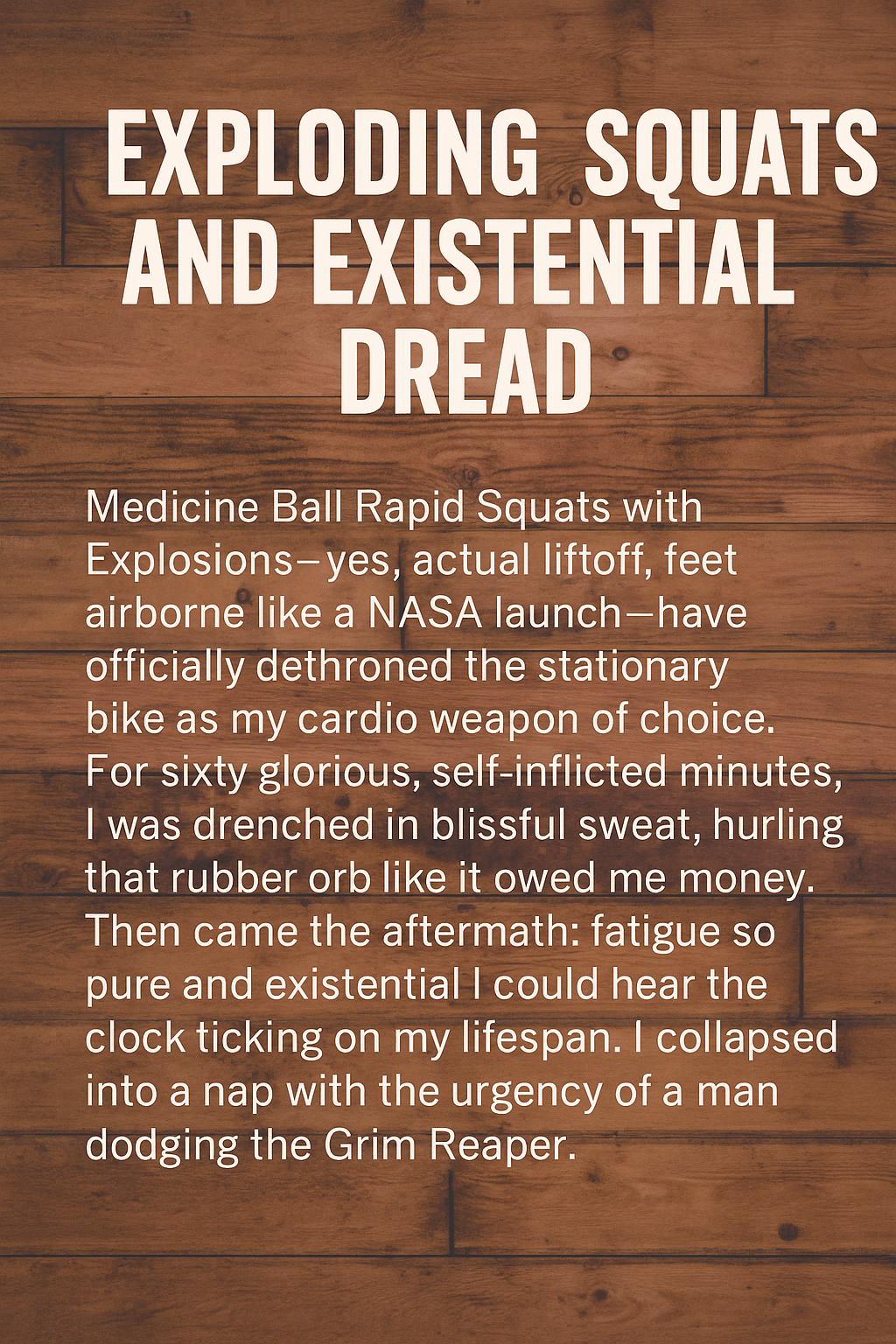

5. I Like Things That Exist in the World

I’m interested in things with friction and form—things you can grip, build, question, deconstruct. Music. Technology. Communication tools. Exercise. Love. Psychological self-sabotage. You know, the good stuff. Happiness, as a subject, has all the density of vapor. It’s more slogan than substance, and when I see it trotted out as a destination, I start scanning for exits.

6. It’s a Hot Tub Full of Bromides

I have no interest in an adult ed class on happiness led by a relentlessly upbeat instructor talking about “mindfulness” and “centeredness” with the fixed grin of someone who has replaced coffee with optimism. I can already hear the buzzwords echoing off the whiteboard. These classes are group therapy in a coloring book—pastel platitudes spoon-fed to the emotionally dehydrated.

7. It’s Not Self-Help. It’s Self-Surveillance

Let’s be honest: a lot of happiness literature feels like a soft form of control. Smile more. Meditate. Adjust your attitude. If you’re not happy, it must be something you’re doing wrong. It’s capitalism’s way of gaslighting your suffering. Don’t look outward—don’t question the system, the politics, the institutions. Just recalibrate your “mindset.” In this sense, the language of happiness is more pacifier than pathfinder.

So yes, Arthur Brooks writes well. He thinks clearly. He’s probably a better person than I am. But his essays on happiness make me recoil—not because they’re wrong, but because they speak a language I no longer trust. I don’t want to be managed, monitored, or optimized. I want to be awake. I want to be challenged. And if I’m lucky, I’ll get to experience the real stuff of life—anger, beauty, confusion, connection—not just a frictionless simulation of contentment.

Happiness can keep smiling from the other side of the screen. I’ve got kettlebells to swing.