In More Than Words: How to Think About Writing in the Age of AI, John Warner points out just how emotionally tone-deaf ChatGPT is when tasked with describing something as tantalizing as a cinnamon roll. At best, the AI produces a sterile list of adjectives like “delicious,” “fattening,” and “comforting.” For a human who has gluttonous memories, however, the scent of cinnamon rolls sets off a chain reaction of sensory and emotional triggers—suddenly, you’re transported into a heavenly world of warm, gooey indulgence. For Warner, the smell launches him straight into vivid memories of losing his willpower at a Cinnabon in O’Hare Airport. ChatGPT, by contrast, is utterly incapable of such sensory delirium. It has no desire, no memory, no inner turmoil. As Warner explains, “ChatGPT has no capacity for sense memory; it has no memory in the way human memory works, period.”

Without memory, ChatGPT can’t make meaningful connections and associations. The cinnamon roll for John Warner is a marker for a very particular time and place in his life. He was in a state of mind then that made him a different person than he was twelve years later reminiscing about the days of caving in to the temptation to buy a Cinnabon. For him, the cinnamon roll has layers and layers of associations that inform his writing about the cinnamon roll that gives depth to his description of that dessert that ChatGPT cannot match.

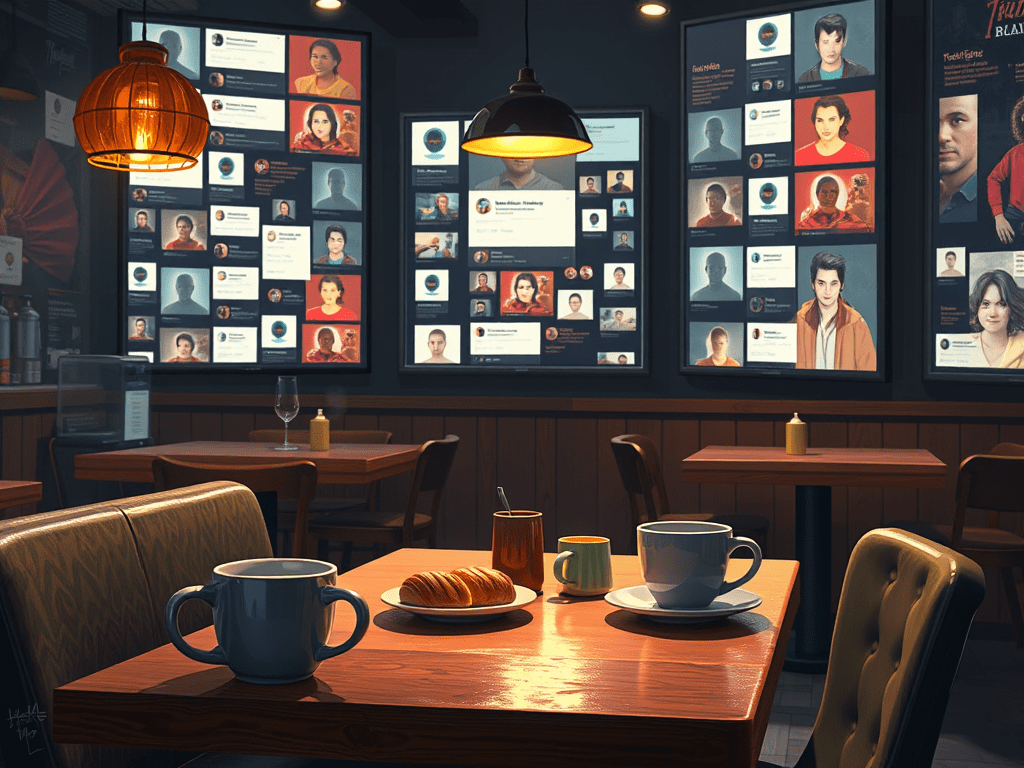

Imagine ChatGPT writing a vivid description of Farrell’s Ice Cream Parlour. It would perform a serviceable job describing the physical layout–the sweet aroma of fresh waffle cones, sizzling burgers, and syrupy fudge; the red-and-white striped wallpaper stretched from corner to corner, the dark, polished wooden booths lining the walls; the waitstaff, dressed in candy-cane-striped vests and straw boater hats, and so on. However, there are vital components missing in the description–a kid’s imagination full of memories and references to their favorite movies, TV shows, and books. The ChatGPT version is also lacking in a kid’s perspective, which is full of grandiose aspirations to being like their heroes and mythical legends.

For someone who grow up believing that Farrell’s was the Holy Grail for birthday parties, my memory of the place adds multiple dimensions to the ice cream parlour that ChatGPT is incapable of rendering:

When I was a kid growing up in the San Francisco Bay Area in the 1970s, there was an ice creamery called Farrell’s. In a child’s imagination, Farrell’s was the equivalent of Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory. You didn’t go to Farrell’s often, maybe once every two years or so. Entering Farrell’s, you were greeted by the cacophony of laughter and the clinking of spoons against glass. Servers in candy-striped uniforms dashed around with the energy of marathon runners, bearing trays laden with gargantuan sundaes. You sat down, your eyes wide with awe, and the menu was presented to you like a sacred scroll. You don’t need to read it, though. Your quest was clear: the legendary banana split. When the dessert finally arrived, it was nothing short of a spectacle. The banana split was monumental, an ice cream behemoth. It was as if the dessert gods themselves had conspired to create this masterpiece. Three scoops of ice cream, draped in velvety hot fudge and caramel, crowned with mountains of whipped cream and adorned with maraschino cherries, all nestled between perfectly ripe bananas. Sprinkles and nuts cascaded down the sides like the treasures of a sugar-coated El Dorado. As you took your first bite, you embarked on a journey as grand and transformative as any hero’s quest. The flavors exploded in your mouth, each spoonful a step deeper into the enchanted forest of dessert ecstasy. You were not just eating ice cream; you were battling dragons of indulgence and conquering kingdoms of sweetness. The sheer magnitude of the banana split demanded your full attention and stamina. Your small arms wielded the spoon like a warrior’s sword, and with each bite, you felt a mixture of triumph and fatigue. By the time you reached the bottom of the bowl, you were exhausted. Your muscles ached as if you’d climbed a mountain, and you were certain that you’d expanded your stomach capacity to Herculean proportions. You briefly considered the possibility of needing an appendectomy. But oh, the glory of it all! Your Farrell’s sojourn was worth every ache and groan. You entered the ice creamery as an ordinary child and emerged as a hero. In this fairy-tale-like journey, you had undergone a metamorphosis. You were no longer just a scrawny kid from the Bay Area; you were now a muscle-bound strutting Viking of the dessert world, having mastered the art of indulgence and delight. As you returned home, the experience of Farrell’s left a lasting imprint on your soul. You regaled your friends with tales of your conquest, the banana split becoming a legendary feast in the annals of your childhood adventures. In your heart, you knew that this epic journey to Farrell’s, this magical pilgrimage, had elevated you to the ranks of dessert royalty, a memory that would forever glitter like a golden crown in the kingdom of your mind. As a child, even an innocent trip to an ice creamery was a transformational experience. You entered Farrell’s a helpless runt; you exited it a glorious Viking.

The other failure of ChatGPT is that it cannot generate meaningful narratives. Without memory or point of view, ChatGPT has no stories to tell and no lessons to impart. Since the days of our Paleolithic ancestors, humans have shared emotionally charged stories around the campfire to ward off both external dangers—like saber-toothed tigers—and internal demons—obsessions, pride, and unbridled desires that can lead to madness. These tales resonate because they acknowledge a truth that thoughtful people, religious or not, can agree on: we are flawed and prone to self-destruction. It’s this precarious condition that makes storytelling essential. Stories filled with struggle, regret, and redemption offer us more than entertainment; they arm us with the tools to stay grounded and resist our darker impulses. ChatGPT, devoid of human frailty, cannot offer us such wisdom.

Because ChatGPT has no memory, it cannot give us the stories and life lessons we crave and have craved for thousands of years in the form of folk tales, religious screeds, philosophical treatises, and personal manifestos.

That ChatGPT can only muster a Wikipedia-like description of a cinnamon roll hardly makes it competitive with humans when it comes to the kind of writing we crave with all of our heart, mind, and soul.

One of ChatGPT’s greatest disadvantages is that, unlike us, it is not a fallen creature slogging through the freak show that is this world, to use the language of George Carlin. Nor does ChatGPT understand how our fallen condition can put us at the mercy of our own internal demons and obsessions that cause us to warp reality that leads to dysfunction. In other words, ChatGPT does not have a haunted mind and without any oppressive memories, it cannot impart stories of value to us.

When I think of being haunted, I think of one emotion above all others–regret. Regret doesn’t just trap people in the past—it embalms them in it, like a fly in amber, forever twitching with regret. Case in point: there are three men I know who, decades later, are still gnashing their teeth over a squandered romantic encounter so catastrophic in their minds, it may as well be their personal Waterloo.

It was the summer of their senior year, a time when testosterone and bad decisions flowed freely. Driving from Bakersfield to Los Angeles for a Dodgers game, they were winding through the Grapevine when fate, wearing a tie-dye bikini, waved them down. On the side of the road, an overheated vintage Volkswagen van—a sunbaked shade of decayed orange—coughed its last breath. Standing next to it? Four radiant, sun-kissed Grateful Dead followers, fresh from a concert and still floating on a psychedelic afterglow.

These weren’t just women. These were ethereal, free-spirited nymphs, perfumed in the intoxicating mix of patchouli, wild musk, and possibility. Their laughter tinkled like wind chimes in an ocean breeze, their sun-bronzed shoulders glistening as they waved their bikinis and spaghetti-strap tops in the air like celestial signals guiding sailors to shore.

My friends, handy with an engine but fatally clueless in the ways of the universe, leaped to action. With grease-stained heroism, they nursed the van back to health, coaxing it into a purring submission. Their reward? An invitation to abandon their pedestrian baseball game and join the Deadhead goddesses at the Santa Barbara Summer Solstice Festival—an offer so dripping with hedonistic promise that even a monk would’ve paused to consider.

But my friends? Naïve. Stupid. Shackled to their Dodgers tickets as if they were golden keys to Valhalla. With profuse thanks (and, one imagines, the self-awareness of a plank of wood), they declined. They drove off, leaving behind the road-worn sirens who, even now, are probably still dancing barefoot somewhere, oblivious to the tragedy they unwittingly inflicted.

Decades later, my friends can’t recall a single play from that Dodgers game, but they can describe—down to the last bead of sweat—the precise moment they drove away from paradise. Bring it up, and they revert into snarling, feral beasts, snapping at each other over whose fault it was that they abandoned the best opportunity of their pathetic young lives. Their girlfriends, beautiful and present, might as well be holograms. After all, these men are still spiritually chained to that sun-scorched highway, watching the tie-dye bikini tops flutter in the wind like banners of a lost kingdom.

Insomnia haunts them. Their nights are riddled with fever dreams of sun-drenched bacchanals that never happened. They wake in cold sweats, whispering the names of women they never actually kissed. Their relationships suffer, their souls remain malnourished, and all because, on that fateful day, they chose baseball over Dionysian bliss.

Regret couldn’t have orchestrated a better long-term psychological prison if it tried. It’s been forty years, but they still can’t forgive themselves. They never will. And in their minds, somewhere on that dusty stretch of highway, a rusted-out orange van still sits, idling in the sun, filled with the ghosts of what could have been.

Humans have always craved stories of folly, and for good reason. First, there’s the guilty pleasure of witnessing someone else’s spectacular downfall—our inner schadenfreude finds comfort in knowing it wasn’t us who tumbled into the abyss of human madness. Second, these stories hold up a mirror to our own vulnerability, reminding us that we’re all just one bad decision away from disaster.

As a teacher, I can tell you that if you don’t anchor your ideas to a compelling story, you might as well be lecturing to statues. Without a narrative hook, students’ eyes glaze over, their minds drift, and you’re left questioning every career choice that led you to this moment. But if you offer stories brimming with flawed characters—haunted by regrets so deep they’re like Lot’s wife, frozen and unmovable in their failure—students perk up. These narratives speak to something profoundly human: the agony of being broken and the relentless desire to become whole again. That’s precisely where AI like ChatGPT falls short. It may craft mechanically perfect prose, but it has never known the sting of regret or the crushing weight of shame. Without that depth, it can’t deliver the kind of storytelling that truly resonates.