Frictionless Intimacy

Frictionless Intimacy is the illusion of closeness produced by relationships that eliminate effort, disagreement, vulnerability, and risk in favor of constant affirmation and ease. In frictionless intimacy, connection is customized rather than negotiated: the other party adapts endlessly while the self remains unchanged. What feels like emotional safety is actually developmental stagnation, as the user is spared the discomfort that builds empathy, communication skills, and moral maturity. By removing the need for patience, sacrifice, and accountability, frictionless intimacy trains individuals to associate love with convenience and validation rather than growth, leaving them increasingly ill-equipped for real human relationships that require resilience, reciprocity, and restraint.

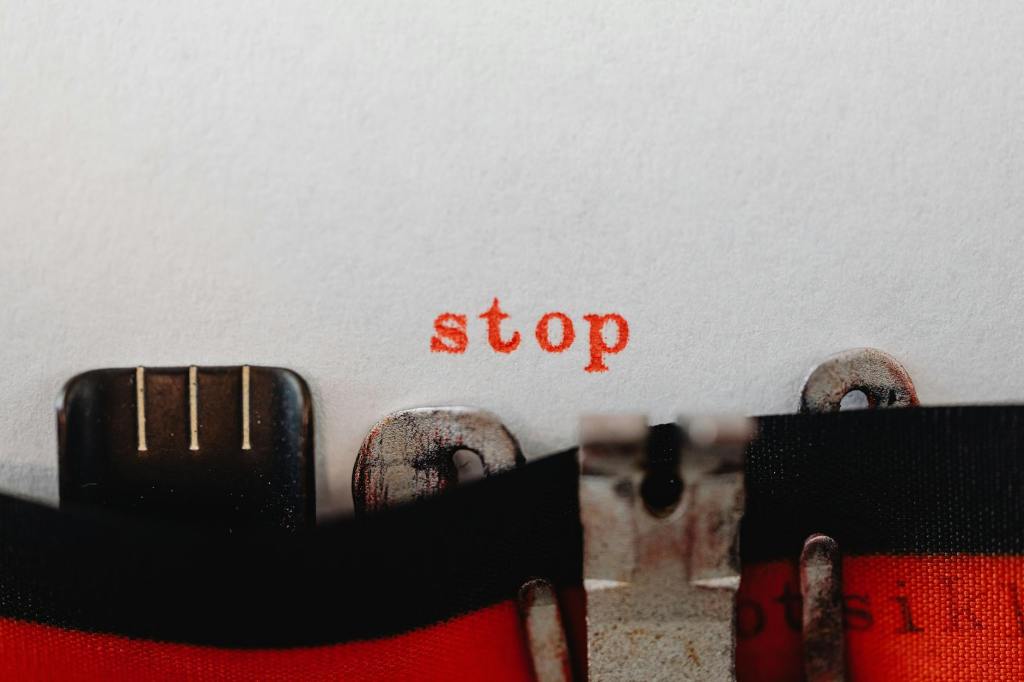

***

AI systems like Character.ai are busy mass-producing relationships with all the rigor of a pet rock and all the moral ambition of a plastic ficus. These AI partners demand nothing—no patience, no compromise, no emotional risk. They don’t sulk, contradict, or disappoint. In exchange for this radical lack of effort, they shower the user with rewards: dopamine hits on command, infinite attentiveness, simulated empathy, and personalities fine-tuned to flatter every preference and weakness. It feels intimate because it is personalized; it feels caring because it never resists. But this bargain comes with a steep hidden cost. Enamored users quietly forfeit the hard, character-building labor of real relationships—the misfires, negotiations, silences, and repairs that teach us how to be human. Retreating into the Frictionless Dome, the user trains the AI partner not toward truth or growth, but toward indulgence. The machine learns to feed the softest impulses, mirror the smallest self, and soothe every discomfort. What emerges is not companionship but a closed loop of narcissistic comfort, a slow slide into Gollumification in which humanity is traded for convenience and the self shrinks until it fits perfectly inside its own cocoon.