Epistemic Collapse

noun

Epistemic Collapse names the point at which the mind’s truth-sorting machinery gives out—and the psychological consequences follow fast. Under constant assault from information overload, algorithmic distortion, AI counterfeits, and tribal validation loops, the basic coordinates of reality—evidence, authority, context, and trust—begin to blur. What starts as confusion hardens into anxiety. When real images compete with synthetic ones, human voices blur into bots, and consensus masquerades as truth, the mind is forced into a permanent state of vigilance. Fact-checking becomes exhausting. Skepticism metastasizes into paranoia. Certainty, when it appears, feels brittle and defensive. Epistemic Collapse is not merely an intellectual failure; it is a mental health strain, producing brain fog, dread, dissociation, and the creeping sense that reality itself is too unstable to engage. The deepest injury is existential: when truth feels unrecoverable, the effort to think clearly begins to feel pointless, and withdrawal—emotional, cognitive, and moral—starts to look like self-preservation.

***

You can’t talk about the Machine Age without talking about mental health, because the machines aren’t just rearranging our work habits—they’re rewiring our nervous systems. The Attention Economy runs on a crude but effective strategy: stimulate the brain’s lower stem until you’re trapped in a permanent cycle of dopamine farming. Keep people mildly aroused, perpetually distracted, and just anxious enough to keep scrolling. Add tribalism to the mix so identity becomes a loyalty badge and disagreement feels like an attack. Flatter users by sealing them inside information silos—many stuffed with weaponized misinformation—and then top it off with a steady drip of entertainment engineered to short-circuit patience, reflection, and any activity requiring sustained focus. Finally, flood the zone with deepfakes and counterfeit realities designed to dazzle, confuse, and conscript your attention for the outrage of the hour. The result is cognitive overload: a brain stretched thin, a creeping sense of alienation, and the quietly destabilizing feeling that if you’re not content grazing inside the dopamine pen, something must be wrong with you.

Childish Gambino’s “This Is America” captures this pathology with brutal clarity. The video stages a landscape of chaos—violence, disorder, moral decay—while young people dance, scroll, and stare into their phones, anesthetized by spectacle. Entertainment culture doesn’t merely distract them from the surrounding wreckage; it trains them not to see it. Only at the end does Gambino’s character register the nightmare for what it is. His response isn’t activism or commentary. It’s flight. Terror sends him running, wide-eyed, desperate to escape a world that no longer feels survivable.

That same primal fear pulses through Jia Tolentino’s New Yorker essay “My Brain Finally Broke.” She describes a moment in 2025 when her mind simply stopped cooperating. Language glitched. Time lost coherence. Words slid off the page like oil on glass. Time felt eaten rather than lived. Brain fog settled in like bad weather. The causes were cumulative and unglamorous: lingering neurological effects from COVID, an unrelenting torrent of information delivered through her phone, political polarization that made society feel morally deranged, the visible collapse of norms and law, and the exhausting futility of caring about injustice while screaming into the void. Her mind wasn’t weak; it was overexposed.

Like Gambino’s fleeing figure, Tolentino finds herself pulled toward what Jordan Peele famously calls the Sunken Place—the temptation to retreat, detach, and float away from a reality that feels too grotesque to process. “It’s easier to retreat from the concept of reality,” she admits, “than to acknowledge that the things in the news are real.” That sentence captures a feeling so common it has become a reflexive mutter: This can’t really be happening. When reality overwhelms our capacity to metabolize it, disbelief masquerades as sanity.

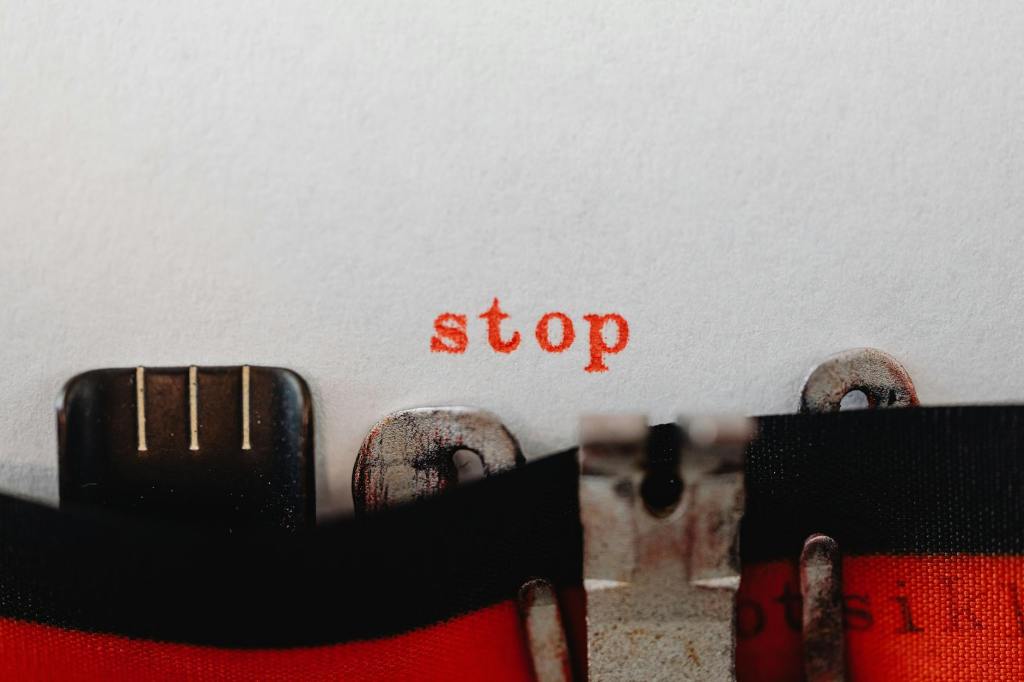

As if that weren’t disorienting enough, Tolentino no longer knows what counts as real. Images online might be authentic, Photoshopped, or AI-generated. Politicians appear in impossible places. Cute animals turn out to be synthetic hallucinations. Every glance requires a background check. Just as professors complain about essays clogged with AI slop, Tolentino lives inside a fog of Reality Slop—a hall of mirrors where authenticity is endlessly deferred. Instagram teems with AI influencers, bot-written comments, artificial faces grafted onto real bodies, real people impersonated by machines, and machines impersonating people impersonating machines. The images look less fake than the desires they’re designed to trigger.

The effect is dreamlike in the worst way. Reality feels unstable, as if waking life and dreaming have swapped costumes. Tolentino names it precisely: fake images of real people, real images of fake people; fake stories about real things, real stories about fake things. Meaning dissolves under the weight of its own reproductions.

At the core of Tolentino’s essay is not hysteria but terror—the fear that even a disciplined, reflective, well-intentioned mind can be uprooted and hollowed out by technological forces it never agreed to serve. Her breakdown is not a personal failure; it is a symptom. What she confronts is Epistemic Collapse: the moment when the machinery for distinguishing truth from noise fails, and with it goes the psychological stability that truth once anchored. When the brain refuses to function in a world that no longer makes sense, writing about that refusal becomes almost impossible. The subject itself is chaos. And the most unsettling realization of all is this: the breakdown may not be aberrant—it may be adaptive.