In eighth grade, Erika Jenkins was every boy’s favorite target—a tall, freckled volleyball player with legs that seemed to go on for miles and a face that couldn’t hide her fear. The boys called her Horse, Giraffe, Hyena, Zebra—an entire menagerie of cruelty. Every morning she had to walk the gauntlet from her locker to the corridor, clutching her books to her chest like a shield, her eyes darting from side to side as if she were trying to survive a nature documentary. She looked like someone bracing for an attack, because she was.

Then summer arrived—and performed a miracle. Her grandmother took her on a Caribbean cruise, and somewhere between the turquoise waves and the buffet line, Erika Jenkins molted. When she returned that fall, she was unrecognizable. The boys at Canyon High buzzed with talk of “The Caribbean Transformation.”

At lunch on the first day, she made her debut. Gone was the awkward, lanky girl. In her place stood someone who could have walked off a shampoo commercial. She wore a sleeveless white linen dress that caught the light, her tan skin glowing like toasted sugar. Her once-flat hair now tumbled over her shoulders in glossy brown waves. Her limbs, once all elbows and knees, now belonged to a young woman who had grown into herself.

The same boys who had brayed at her like hyenas now worshiped her like pilgrims before a shrine. They tripped over themselves to compliment her, their awe soon sliding into the same loutish cruelty—just with a new vocabulary. The tone changed from mockery to hunger, but the malice was the same. By October, Erika Jenkins vanished—transferred, rumor had it, to a small private school where maybe she could breathe.

I was furious—but not for noble reasons. I had finally worked up the nerve to ask her out. And now she was gone, like a dream that evaporates the moment you wake.

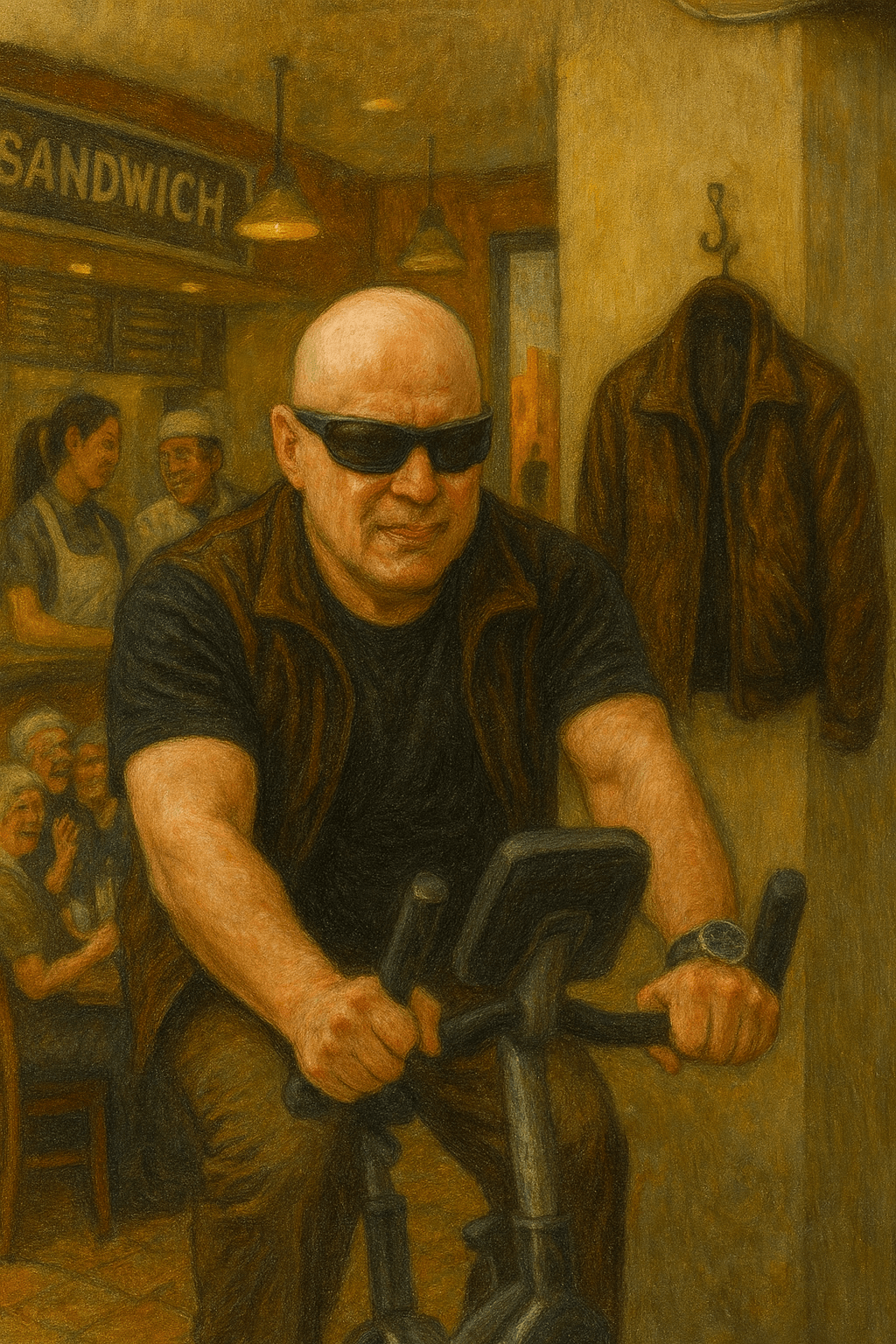

That night, I asked Master Po why her story hadn’t followed the script of The Ugly Duckling. “Why wasn’t there a happy ending?” I asked.

“Because, Grasshopper,” he said, “not all fairytales are true. The boys mocked her when she was an ‘ugly duckling,’ and they mocked her again when she became a ‘beautiful swan.’ Only their weapons changed—from insult to lust. They remained prisoners of their malice. It was they, not she, who failed to evolve.”

He said this with a sharpness I wasn’t used to. “But I never teased her,” I protested. “Not once.”

“Do not congratulate yourself for being less vile than the wicked,” he said. “You still measured your worth by their ugliness. You did not defend her. You simply waited for your turn to possess her beauty. Her radiance blinded them—and you as well.”

“Are you saying I’m no better than they are?”

“I am saying,” Master Po said, “that even a moth believes itself noble until it burns in the flame. I can already see you falling from the sky.”

He was right, of course. My heartbreak wasn’t about Erika’s suffering—it was about my own loss. I didn’t mourn her pain. I mourned my missed opportunity to bask in her glow. Even in my sympathy, I was self-absorbed. Master Po saw the rot beneath my pity.

He always did.