When you’re married, you’ve closed the deal. You’ve made your public and private commitment to another person. Yet, as Phil Stutz points out in Lessons for Living, this loyalty oath collides with a culture that insists there’s always a better deal waiting. It’s our supposed “divine right” to find that deal, to “look outside ourselves for more.” In other words, FOMO infects the way we relate to our spouses. Stutz writes: “The result is a frenzy of activity, powered by the fear of missing something, which exhausts us emotionally and leaves us spiritually empty.”

As a therapist to Hollywood’s wealthy actors and producers, Stutz sees people in perpetual pursuit of “bigger and better”—newer houses, flashier careers, younger spouses once they’ve “made it.” They want to “trade up,” convinced they deserve it. But what they crave isn’t a flesh-and-blood partner. It’s a “fantasy companion,” a frozen image of perfection that bears no resemblance to real life. As Stutz notes of one patient, a successful actor: “What he was really looking for was someone with the magical ability to change the nature of reality.”

Why do so many of us want to change reality? Because reality is messy, uncertain, painful, and demands labor of mind and spirit. Consumer culture promises to scrub away that mess and deliver a “frictionless” existence. It sells us the Warm Bath: a world of perpetual pleasure and no conflict. But the Warm Bath is an adolescent fantasy—an illusion that reality will mold itself to our most immature notions of happiness.

This fantasy always collapses. No “fantasy companion” exists, and even if one did, the Warm Bath curdles into hell. Experiences flatten, pleasures dull, the hedonic treadmill spins us into numbness, and from numbness we fall into rage—blaming the fantasy companion for failing to save us.

Stutz argues we must abandon the fantasy of love—a stagnant “perfect” photograph—for the messier, real version: alive, unpredictable, and demanding effort. “To put it simply,” he writes, “love is a process. All processes require endless work because perfection is never achieved. Accepting this fact is not thrilling, but it is the first step to happiness. You can work on finding satisfaction in your relationship the same way you’d work on your piano playing or your garden.”

So if you spend your days marinating in salacious fantasies and stoking your FOMO with consumer culture, you’re killing reality while feeding fantasy. And because you’re putting no work into your relationship, entropy sets in. Bonds fray, affection curdles, and instead of taking responsibility, you blame your partner and draft your exit strategy.

To keep his patients from falling into this trap, Stutz prescribes three tools.

The first is Fantasy Control. Fantasies, he warns, can grow “long and involved” until they compete with real relationships. Steely Dan’s “Deacon Blues” comes to mind. Its narrator is a suburban mediocrity who dreams himself into an edgy artist and seducer of women. Fans saw themselves in him, but the song is ironic: a portrait of a fallen man propping up a drab life with self-mythology. Such fantasies, Stutz says, “hold a tremendous amount of emotional energy.” The more energy you pour into a phantom partner, the less you have for your real one. When fantasies become sexual, the drain is worse. Stutz insists that when fantasies consume you, you must learn to interrupt them. “You’ll resent this at first,” he writes, “but each time you come down to earth you’re telling yourself that you are a committed adult who is strong enough to face reality. This will make you more satisfied with yourself, a precondition to becoming satisfied with any partner.”

If you’re a boomer like me, this may sound like heresy. Raised in the 60s and 70s, we were taught to unleash the Id, to celebrate fantasies as expressions of the “true self.” The musical Hair didn’t just glorify wild locks but turned them into a metaphor of rebellion against authority. Hugh Hefner and Xaviera Hollander gave us ribald lifestyles to envy. Thomas Harris’s I’m Okay, You’re Okay blessed us with permission to indulge. And the cultural mantra was simple: “Let it all hang out!”

But Stutz, a boomer himself, has watched fantasies devour his patients. His conclusion is blunt: curbing sexual fantasy is a crucial step toward adulthood and a stronger bond with one’s partner.

The second tool is Judgment. Fixate on a fantasy partner and you suspend critical thought, surrendering to false perfection. You also sharpen your critique of your real partner until both fantasy and reality are grotesquely warped. To break free, Stutz says, you must recognize this distortion and choose a loving path over a fantasy path. “The process of loving requires that you catch yourself having these negative thoughts and dissolve them from your mind, replacing them with positive ones. You must actively construct thoughts about their good attributes, and let these thoughts renew feelings of attraction toward them.” This habit builds gratitude, restores attraction, and replaces helplessness with control.

Reflecting on this, I recall Tim Parks’s essay “Adultery,” in which he describes a friend’s affair that destroyed his marriage. Parks likens sexual passion to a raging river that demolishes everything in its path, while domestic life is the quieter work of nest-building. The two impulses are locked in eternal conflict. Some people cannot resist hurling themselves into the river, even knowing it will consume them.

To pull people out of that river, Stutz prescribes his third tool: Emotional Expression. Here self-expression works in reverse. Just as smiling can make you happier, acts of tenderness can make you feel tender. Stutz advises: when you’re alone with your partner, speak and touch them as if they are desirable. Do this consistently and not only will you find them more attractive, they’ll begin to find you more attractive too.

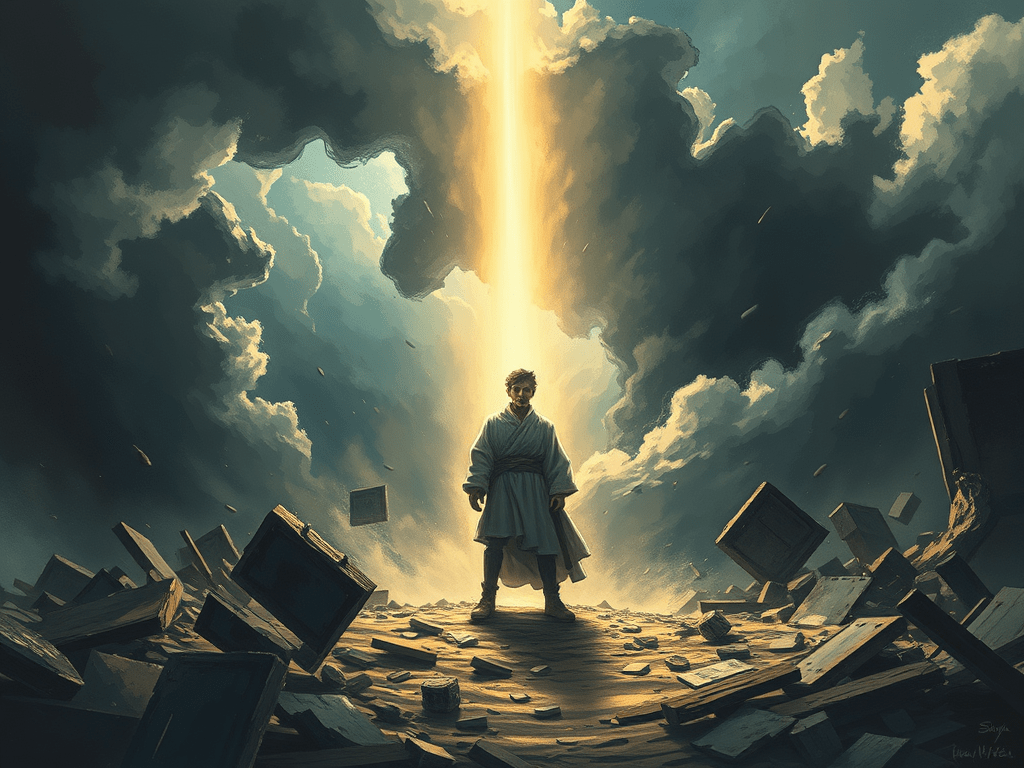

It may sound counterintuitive. Who “works” for attraction? But that is Stutz’s point: love is work. Excessive fantasy, meanwhile, is infidelity—not only to your spouse, but to your adult self. Stay shackled to your adolescent hedonist, and like Lot’s wife, you’ll turn into a pillar of salt.