My dear, respectable neighbors, the Pattersons have forced me to contend with Neighborplexity. Let me explain. For years, I lived in blissful harmony with these upstanding citizens—the kind of people who proudly displayed their New Yorker subscriptions and NPR tote bags like badges of intellectual honor. We had an unspoken pact, a mutual understanding that we were members of the Smart People’s Society, where the TV was reserved for documentaries, award-winning dramas, and the occasional indie film that required subtitles and a dictionary to understand.

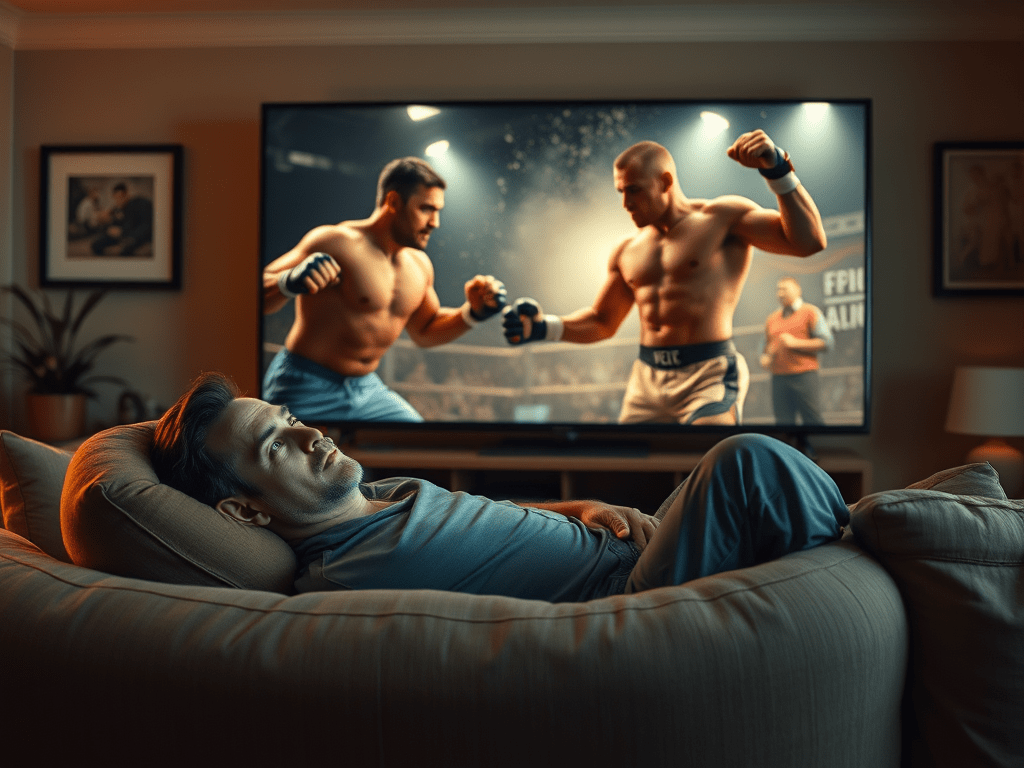

But then, one evening, as I casually glanced out my window—just a harmless peek, really—I saw something so grotesque, so utterly incomprehensible, that it shook me to my core. There, through the open window of my once-revered neighbors, I saw them glued to the screen—not just any screen, but one streaming a TV show so mind-numbingly lowbrow it made reality itself seem like a parody. My brain went into full-blown meltdown. Could it be? Were they actually watching Love Island?

I blinked, hoping I’d misinterpreted the scene, but no—the horror was all too real. My neighbors, those paragons of taste and intellect, were indulging in what could only be described as televised garbage. I was struck down by a case of Neighborplexity: that gut-wrenching, mind-twisting moment when you realize you might not know the people next door at all. Suddenly, my world was flipped upside down. Had they always been this way? Were those book club meetings just a ruse, a clever cover-up for their secret love affair with trash TV? I felt like I’d just discovered that the Michelin-starred chef who lived down the block actually preferred dining on Spam straight out of the can.

I thought we were united in our disdain for anything that wasn’t at least 95% fresh on Rotten Tomatoes. But now? Now, I wasn’t so sure. How could they betray me like this? Was every dinner party, every casual chat about the latest literary masterpiece, just a well-orchestrated charade? My mind spun as I tried to reconcile the image of these seemingly cultured, well-spoken people with the reality of them willingly watching—gasp—that show.

What do I do now? How do I move forward? Can I ever look them in the eye again, or will I be forever haunted by this dark revelation, this unraveling of the fabric of my once-idyllic neighborhood? All because of one dreadful, unforgivable act of poor taste on TV. Love Island, of all things. The horror! The betrayal! The absolute audacity!

To get through this ordeal, I must have a clear definition of Neighborplexity and study the coping mechanisms to help me deal with this. So here we go.

Neighborplexity (n.): The psychological whiplash that occurs when your carefully curated perception of your neighbors—those tote-bag-wielding, podcast-quoting, fair-trade-coffee-brewing intellectuals—is shattered by the revelation that they voluntarily watch garbage television. One moment you’re nodding in mutual disdain over a New Yorker cartoon; the next, you’re watching them binge Love Island with the hungry intensity of someone decoding the Dead Sea Scrolls. Neighborplexity induces spiritual vertigo, trust erosion, and the overwhelming sense that the social fabric of your ZIP code has been irreparably torn by sequins, fake tans, and manufactured drama. It is, in essence, a full-blown existential crisis brought on by a neighbor’s taste in television.

7 Coping Mechanisms for Surviving Neighborplexity:

- Curated Amnesia – Tell yourself you didn’t see it. What open window? What TV screen? As far as you’re concerned, they were watching a Ken Burns documentary about soil.

- Projection Therapy – Assume it was ironic. They’re studying Love Island for a sociological thesis titled The Semiotics of Spray Tan.

- NPR Overdose – Immediately listen to four consecutive episodes of Fresh Air to flush out any lingering trash-TV toxins.

- Visual Recalibration – Replace your neighbor’s face with Tilda Swinton’s. At all times. It helps.

- Sarcastic Enlightenment – Convince yourself this is actually a deeper form of taste. Maybe Love Island is postmodern performance art and you’re the unsophisticated one.

- Emergency Sumatra Deployment – Brew the darkest, most self-righteous coffee you can find and sip it slowly while rereading Proust. This reminds you who you really are.

- Petty Book Club Coup – At the next meeting, accidentally bring up Love Island as a joke and watch their faces. Gauge their guilt. Proceed accordingly with social sanctions or passive-aggressive charcuterie.