Essay Prompt 1:

Lost Boys: Masculinity and Disconnection in the Age of the Algorithm

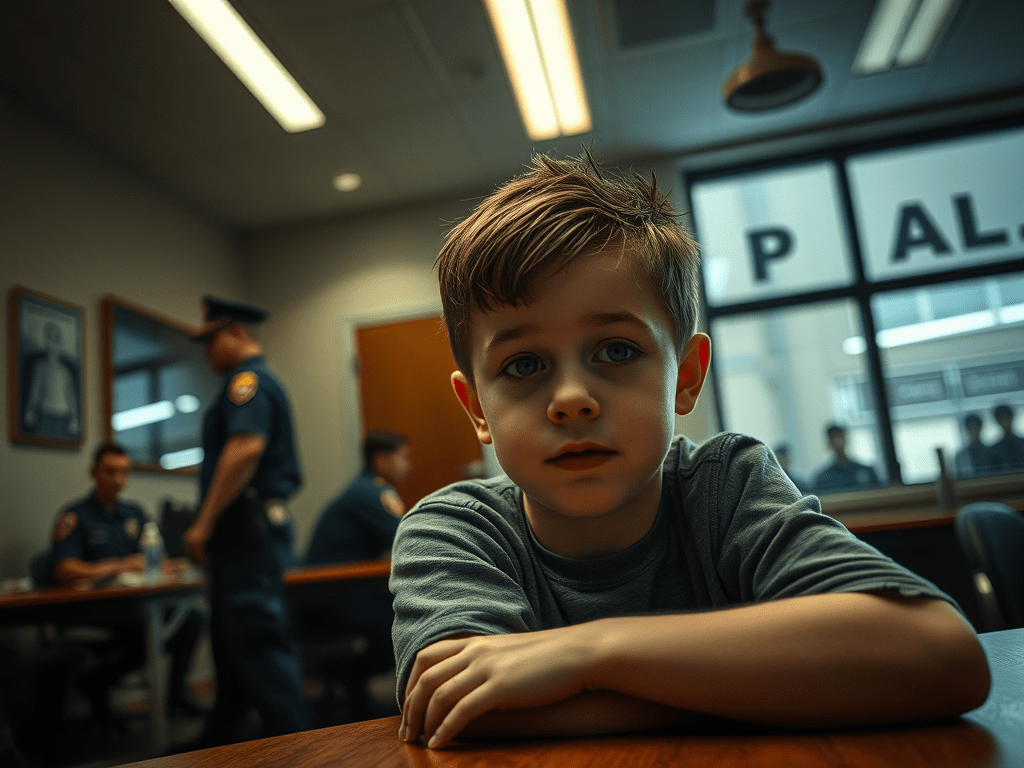

The Netflix series Adolescence portrays young men drifting into emotional isolation, digital fantasy, and performative aggression. Write a 1,700-word argumentative essay analyzing how the series presents the crisis of masculinity in the digital age. How does the show portray the failure of institutions—schools, families, mental health systems—to support young men? In what ways do online subcultures offer a dangerous substitute for real intimacy, guidance, and identity?

Your essay should examine how internet platforms and influencer culture warp traditional male development and how Adolescence critiques or complicates the idea of a “lost generation” of young men.

Essay Prompt 2:

Digital Disintegration: How the Internet Erodes the Self in Adolescence*

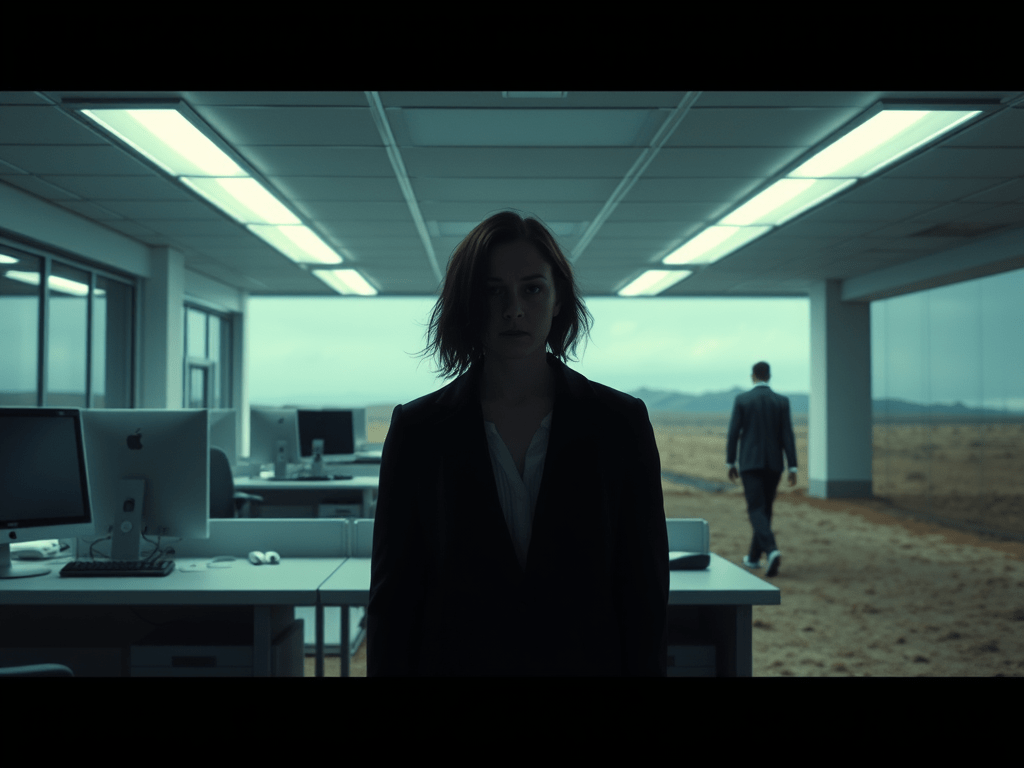

In Adolescence, young men vanish into screens—physically present but psychologically absent, caught in loops of gaming, porn, self-help gurus, and nihilistic memes. Write a 1,700-word analytical essay examining how the show depicts identity erosion, emotional numbness, and digital escapism. Consider how the show portrays online life not as connection, but as a kind of derealized limbo where development stalls and real-world stakes disappear.

Your argument should explore the consequences of a generation shaped by dopamine loops, digital avatars, and constant surveillance. What does Adolescence suggest about what is being lost—and who benefits from that loss?

Essay Prompt 3:

From Memes to Militancy: Radicalization and the Internet’s Hold on Young Men

The Netflix series Adolescence captures the quiet drift of boys into corners of the internet that begin as humor and end in extremism. In a 1,700-word argumentative essay, analyze how the series depicts the pipeline of online radicalization—from ironic memes and manosphere influencers to conspiracy theories and hate movements. What conditions—emotional, economic, social—make these boys susceptible? What does the series suggest about how the algorithm reinforces this spiral?

Your essay should examine how humor, loneliness, and status anxiety are manipulated in online culture—and what Adolescence says about the consequences of letting these forces grow unchecked.

10-Paragraph Essay Outline

(This outline works across all three prompts with slight adjustments for emphasis.)

Paragraph 1 – Introduction

- Hook: Open with a striking scene or character arc from Adolescence that captures the crisis.

- Define the core problem: the disappearance of young men into digital worlds that seem realer than reality.

- Preview key themes: emotional alienation, digital addiction, toxic masculinity, radicalization, algorithmic control.

- Thesis: Adolescence shows that the internet is not just stealing time or attention—it’s restructuring identity, disrupting development, and creating a generation of young men lost in curated illusions, commodified rage, and emotional isolation.

Paragraph 2 – The Vanishing Boy: Emotional Disconnection

- Explore how Adolescence shows young men struggling to express vulnerability or ask for help.

- Analyze scenes of family miscommunication, school apathy, and emotional shutdown.

- Argue that their online retreat is a symptom, not a cause—at least initially.

Paragraph 3 – The Internet as Surrogate Father

- Analyze how the show depicts YouTube mentors, TikTok alphas, or Discord tribes stepping in where real mentors are absent.

- Show how authority figures online offer structure—but often twist it into aggression or control.

- Connect to broader anxieties about masculinity and belonging.

Paragraph 4 – The Addictive Loop

- Detail how characters in the series are shown compulsively scrolling, gaming, watching, or optimizing themselves.

- Introduce the concept of dopamine loops and algorithmic reinforcement.

- Show how pleasure becomes numbness, and time becomes meaningless.

Paragraph 5 – The Meme Path to Extremism (for Prompt 3 or with minor tweaks)

- Trace how irony, meme culture, and dark humor act as gateways to more dangerous content.

- Analyze how Adolescence shows the blurring line between trolling and belief.

- Suggest that humor is weaponized to disarm skepticism and accelerate radicalization.

Paragraph 6 – The Crisis of Identity and Selfhood

- Argue that the series portrays the internet as a space where boys create avatars, not selves.

- Highlight characters who lose track of real-world relationships, ambitions, or even their physical bodies.

- Introduce the concept of identity disintegration as a psychological cost of digital immersion.

Paragraph 7 – The Algorithm as a Character

- Examine how Adolescence treats the algorithm almost like a silent antagonist—shaping behavior invisibly.

- Show how it feeds what boys already fear or desire: status, control, escape, attention.

- Reference scenes where characters are shown spiraling deeper without ever intending to.

Paragraph 8 – Counterargument: Isn’t the Internet Also a Lifeline?

- Acknowledge that some online spaces provide connection, community, or creative expression.

- Rebut: Adolescence doesn’t demonize the internet—but shows what happens when it becomes a substitute for real-life development rather than a supplement.

- Argue that the problem is the absence of balance, mentorship, and media literacy.

Paragraph 9 – Who Benefits from the Lost Boy Crisis?

- Examine the political and economic systems that profit from male alienation: influencers, ad platforms, radical networks.

- Argue that male loneliness has been commodified, gamified, and monetized.

- Suggest that the real villains aren’t boys—but the systems that prey on them.

Paragraph 10 – Conclusion

- Return to your original image or character.

- Reaffirm thesis: Adolescence is a warning—not about tech itself, but about what happens when society abandons boys to find meaning, manhood, and identity from the algorithm.

- End with a call: rescuing the “lost boys” means reconnecting them to something more real than a screen.

Three Sample Thesis Statements

Thesis 1 – Psychological Focus (Prompt 2):

In Adolescence, the disappearance of young men into screens isn’t just a behavioral issue—it’s a crisis of selfhood, where boys no longer develop real identities but become trapped in algorithmically reinforced loops of fantasy, shame, and emotional numbness.

Thesis 2 – Masculinity Focus (Prompt 1):

Adolescence portrays the internet as a dangerous surrogate father to young men—offering distorted versions of masculinity that promise power and belonging while deepening their emotional alienation and social disconnection.

Thesis 3 – Radicalization Focus (Prompt 3):

Through its depiction of ironic memes, online influencers, and algorithmic descent, Adolescence reveals how internet culture radicalizes young men—not through direct coercion, but by turning humor, loneliness, and masculinity into tools of manipulation.

Would you like scaffolded source materials, suggested secondary readings, or possible titles for these essays?