You remembered the first episode of I Dream of Jeannie. Major Tony Nelson—square-jawed astronaut, man of science—crash-landed on a remote island after his space capsule, Stardust One, veered off course. There, buried in the sand like a cursed treasure, he found a mysterious bottle. And then—whoosh—a plume of bluish vapor, and out popped Jeannie: blonde, barefoot, bewitching, and hell-bent on fulfilling his every wish. Tony blinked. Maybe it was a hallucination. Maybe his oxygen-deprived brain was conjuring fantasies. Whatever the case, he wasn’t buying it. He was trained to distrust magical thinking, and Jeannie, glittering and obedient, was the definition of a dangerous shortcut.

You, on the other hand, were no Tony Nelson. You were a teenage Olympic weightlifter and amateur bodybuilder, sprawled out in your bedroom flipping through a muscle magazine, fully hypnotized by the promise of the next miracle breakthrough. You had just finished an article on “progressive resistance training”—a phrase that gave you a warm little shiver of purpose. You divided the world into two kinds of people: those who were progressing and those who were stagnating in mediocrity. You were dead-set on being in the first camp.

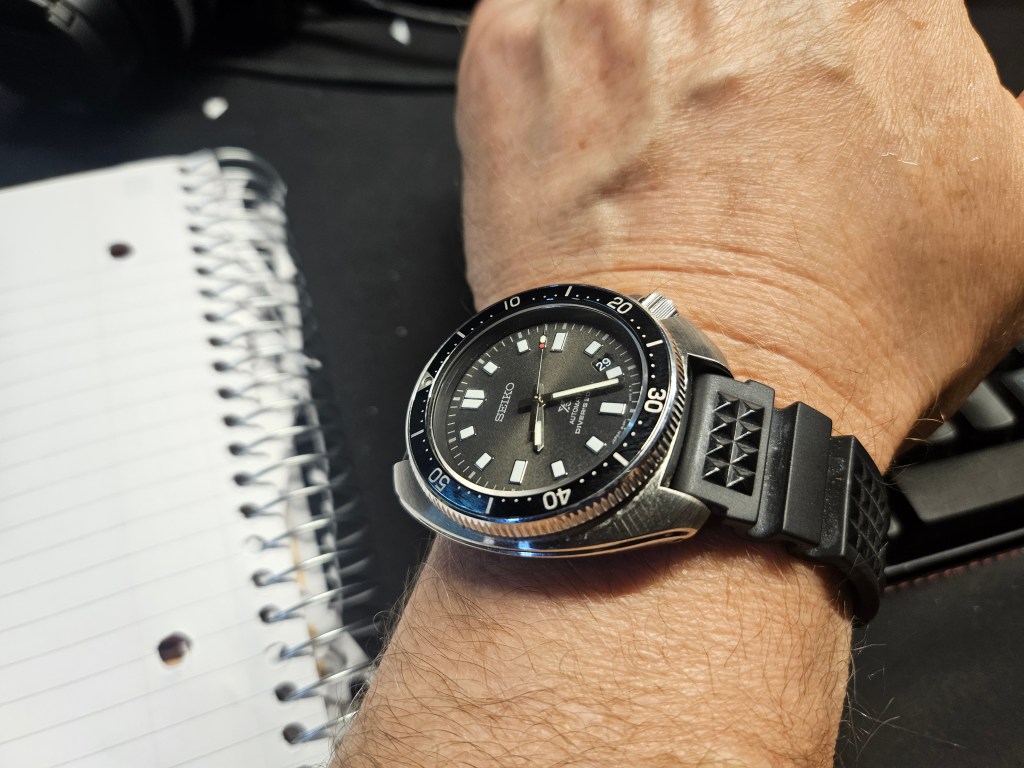

The article ended, but the real magic was in the ads: potions, powders, pulleys, and contraptions promising titanic biceps, superhuman abs, and the sculpted torso of a Greek statue. One ad hit you right in the hypothalamus—the Bullworker. A three-foot rod of steel and plastic, with green-handled grips and bowstring cables. It looked like a cross between a medieval torture device and a Jedi weapon. A bodybuilder in the ad flexed beside it, veins like roadmaps and pecs like dinner plates. It cost forty-five bucks—a king’s ransom. You had to have it.

So you marched into the living room where your dad was nursing a beer and watching football. You handed him the ad.

“What do you think?”

Your dad—a flinty ex-infantryman with a buzz cut, a jaw like a chisel, and a fading “MICHAEL” tattoo on his biceps—glanced at the page like it was a bar tab he didn’t remember running up. “You want muscles?” he said. “Pull weeds. Mow the lawn. Clean gutters. Chop wood.”

“Dad, I’m serious. This would supplement my real workouts.”

He looked again, then sighed. “It’s junk. Slick marketing. But if you want to waste your allowance, it’s your choice.”

You told him you were short on cash.

“Then save up. Make sacrifices. And do your research. If you dig a little deeper, I bet you’ll want it less.”

“Why?”

“Haven’t you heard of Sturgeon’s Law?”

“No.”

“Ninety-nine percent of everything is bullshit. That includes this gadget. Remember that martial arts program you ordered? Twenty bucks for a pamphlet with stick figures doing karate poses. Bullshit. Due diligence, son—that’s your shield.”

“What’s due diligence?”

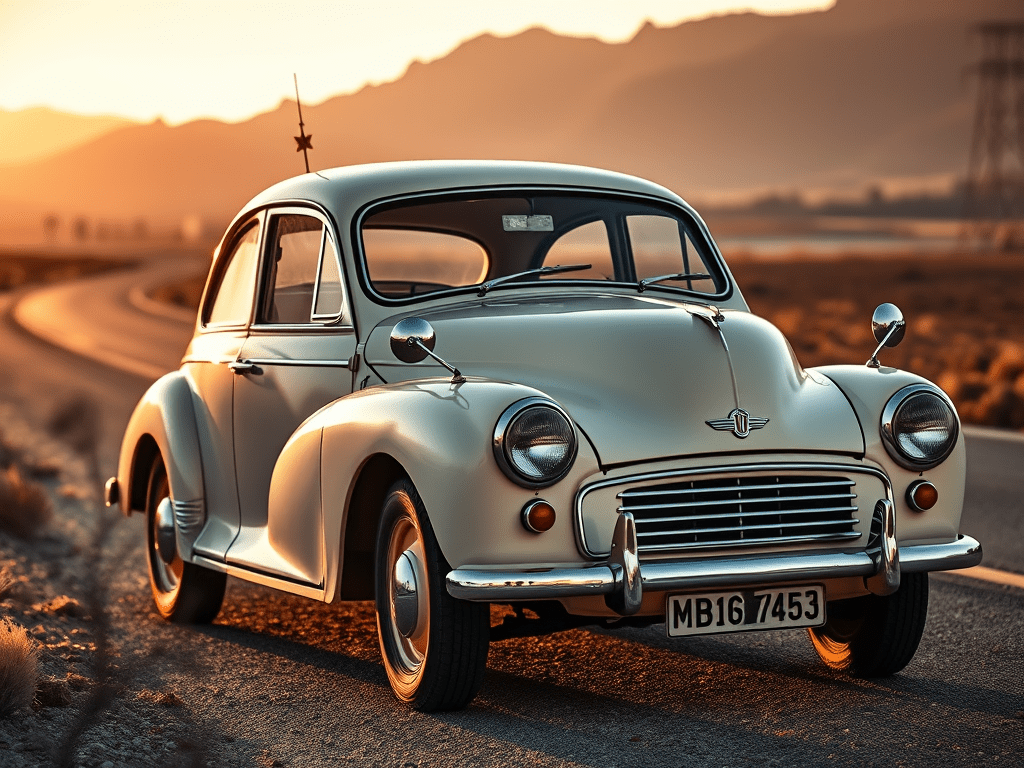

“Thorough investigation. Weighing the pros and cons. Kicking the tires before you buy the clunker. Most things don’t survive scrutiny. Always be quick to save your money and slow to spend it. You got that?”

“Yes, Dad.”

Not exactly in the mood for football after that, you trudged back to your room and cracked open another muscle magazine, drinking in the endless parade of promises. “Gain more muscle than you ever dreamed of,” one ad proclaimed.

And Jeannie was back. Not in her bottle—she was in your brain now. She was the fantasy of every easy answer, every too-good-to-be-true claim. The allure of Jeannie wasn’t just her beauty or her servility—it was her offer of instant gratification, with no price tag except your dignity.

That was the whole premise of the show: Tony Nelson didn’t trust Jeannie because he was smart enough to know that panaceas always come with fine print. But you weren’t that smart yet. You still believed—just a little—that this or that device, powder, or program might turn you into a demigod.

You wanted your gains.

The Bullworker failed you–but it wasn’t just a piece of overpriced cable-tension nonsense. It was a monument to your teenage fantasy: that somewhere, somehow, a portable contraption could carve you into Hercules without the burden of sweat, setbacks, or iron plates. The device itself was a dud—a clunky plastic rod with big promises and no payoff—but the idea of the Bullworker had teeth. A chiseled physique, ready to go, no gym required? It was the dream distilled. What you got instead was a hard truth: even when an idea crashes and burns in practice, some illusions are simply too seductive to abandon.