Chapter 6 of The Timepiece Whisperer

At 6 a.m., I rose like a guilty priest on purge day and loaded my Honda Accord with a museum of failure. Each item whispered its own shame: busted radios that once sang, fans that blew nothing but despair, fossilized laptops gasping through Windows XP, iPads ghosted by iOS updates, a humidifier that wheezed its final death rattle in 2018, and a landmine of corroded batteries that could’ve earned me a write-up from the EPA.

By 8:00, I was cruising down the 110 South, my car bloated with the technological detritus of a man who once believed that stuff—stuff!—might soothe an inner void. I exited Pacific Avenue and found myself crawling through a wasteland of rebar, chain-link fences, and brush thick enough to hide a body or two. It was less Los Angeles and more post-apocalyptic novella. A landscape haunted by discarded dreams and the occasional tented soul whose only offense was being born poor.

After a slow-motion bounce over some railroad tracks, I veered down a bleak gravel path until I arrived at 8:50 to find a tarp flapping over what I assume someone dared to call a facility. It looked like a wedding tent designed by Satan’s party planner, squatting in front of a cinder-block warehouse that smelled like ozone and bureaucratic indifference.

Ahead of me, a small line of sedans idled like supplicants outside a radiation baptism. Signs warned against bringing poisons, rotting food, firearms, explosives, and—oddly—crop waste. Another sign warned me not to exit my vehicle, eat, or drink, presumably because the combination of trail mix and lithium-ion residue could create a chemical lovechild that incinerated San Pedro.

A silver SUV from Washington State attempted to cut the line, realized it had wandered into the wrong apocalypse, and peeled out in a plume of toxic dust that settled on our windshields like the aftermath of a low-budget nuke.

By 9:00, the caravan had doubled. My rearview mirror showed a parade of shame stretching down the gravel like a funeral procession for the Age of Gadgets. Then she arrived—a smiling woman in an orange vest and clip-on radio. Clipboard in hand, she went car-to-car like a cheerful customs agent at the border of human depravity. When she got to me, I rattled off my cargo. Her nod was practiced. I suspect her real job was twofold: assess whether I was harboring illegal pesticides, and determine if I looked like the kind of man who’d stuff a body under an old humidifier.

Eventually, I popped my trunk. Men in uniforms descended with the solemnity of pallbearers. They removed the items with clinical grace, not a single eyebrow raised at my hoarder shame. I thanked them. They nodded like undertakers who’d buried a thousand dreams before mine.

Lighter by fifty pounds and several psychic burdens, I pulled away, my soul humming with moral superiority and the faint possibility of radiation poisoning. For a brief moment, I felt whole.

Then came the craving.

The Seiko Astron.

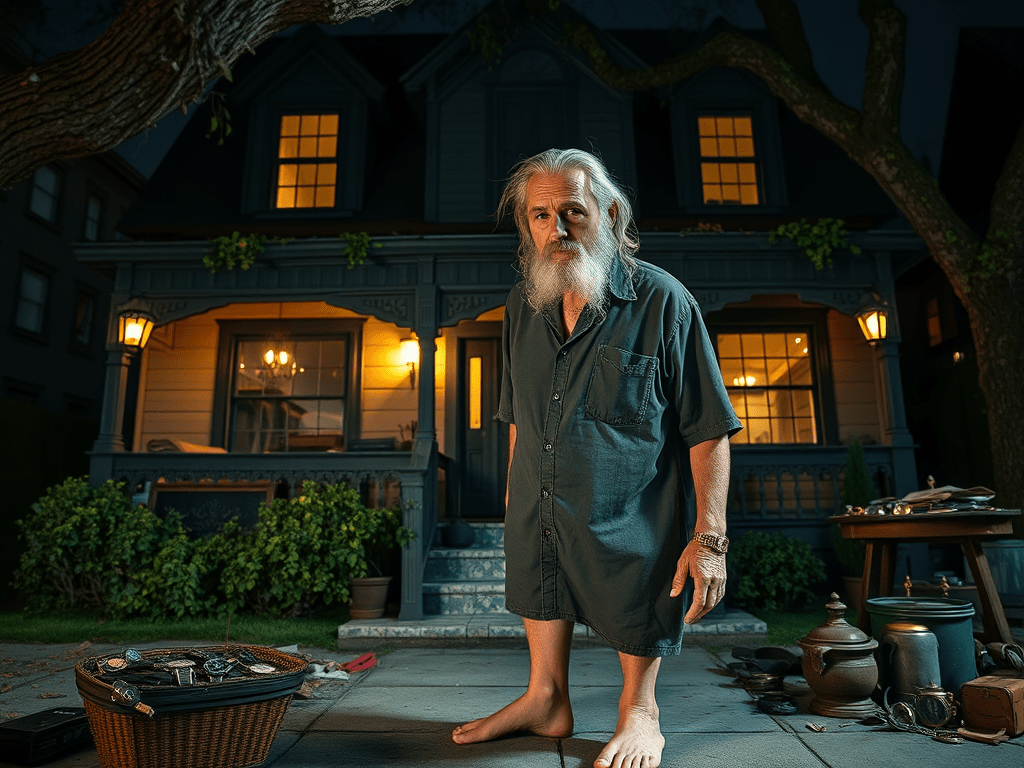

The Watch Master had warned me. Had pleaded for restraint. But there it was again, the whisper in my mind, the itch in my wrist. By the time I got home, I was already spiraling. So I returned to the Watch Master’s house for counsel, but his front door was answered by a red-bearded mountain of a man who looked like he’d just wandered out of a Nordic crime novel.

“Josh,” he said, extending a paw. “I’m the Timepiece Whisperer.”

“What happened to the Watch Master?”

“Dead. Stomachache. Went to bed and never woke up.”

“And you’re… what, the sequel?”

“That’s for you to decide.”

Josh made me an iced coffee, honey and cinnamon. It tasted like guilt sweetened with denial.

We sat at the kitchen table, a graveyard of coffee rings and philosophical despair.

“So what’s troubling you, my friend?”

“I’m almost sixty-four. I own seven watches. I want an eighth. Am I doomed?”

He slurped his drink, crunched an ice cube, and nodded solemnly.

“That depends. Are we talking about eight timepieces? Or eight identities, eight moods, eight regrets?”

I blinked.

He leaned forward. “If you’re still hunting, still haunted, then yes—eight is too many. You don’t have a collection. You have a symptom. But if you’ve made peace—if each watch has its rightful place in your little opera of masculinity—then eight is a symphony. A curated exhibit. A spiritual wardrobe.”

Then he tilted his head. “The real question is: Are you wearing the watches, or are they wearing you?”

I wilted. I wanted to shrink into the upholstery.

“I want the Astron to be the closer. I want to stop at eight. But history tells me I won’t. I go through the honeymoon, get bored, scratch the itch with another watch, and end up miserable. My collection isn’t a triumph. It’s a cry for help.”

Josh chuckled, then howled, then nearly fell off his chair.

“Now we’re getting somewhere. You think this is about timepieces? No, my friend. This is about you.”

Then he called for backup.

First came John, a zombie in slippers with bags under his eyes deep enough to hold grief. “Sell everything,” he said, “and get a Tudor Pelagos. End of story.” Then he stared at his slipper hole like it owed him money and shuffled off.

Then came Gary, a cheerful human protein shake in a Lycra tracksuit.

“Let the man buy the Astron,” he chirped. “Make it eight. Just get him a sponsor, a support group, maybe a hotline. The poor bastard needs this.”

Then John stormed back, furious. “I said one watch!”

Words escalated. Soon they were locked in a full-blown wrestling match, crashing into the walls like toddlers in a padded room. Josh laughed like a man watching Fight Club on loop and eventually threw both of them into the basement.

He stood at the door, listening to the thumps and groans like it was jazz.

“That,” he said, his eyes shining, “is the debate. One watch or many. Order or chaos. Simplicity or delirium.”

I got up to leave.

“What’s the rush?” he asked.

“I’ve seen enough.”

“You’ll be back.”

“What makes you so sure?”

Josh smiled. “Because you’re desperate.”