Merrickel T. Pettibone sat with a glare, Two hundred essays! All posted with flair. He logged into Canvas, his tea steeped with grace, Then grimaced and winced at the Uncanny Face.

The syntax was polished, the quotes were all there, But something felt soulless, like mannequins’ stare. He scrolled and he skimmed, till his stomach turned green— This prose was too perfect, too AI-machine.

He sipped herbal tea from a mug marked “Despair,” Then reclined in his chair with a faraway stare. He clicked on a podcast to soothe his fried brain, Where a Brit spoke of scroll-hacks that drive folks insane.

“Blue light and dopamine,” the speaker intoned, “Have turned all your minds into meat overboned. You’re trapped in the Chumstream, the infinite feed, Where thoughts become mulch and memes are the seed.”

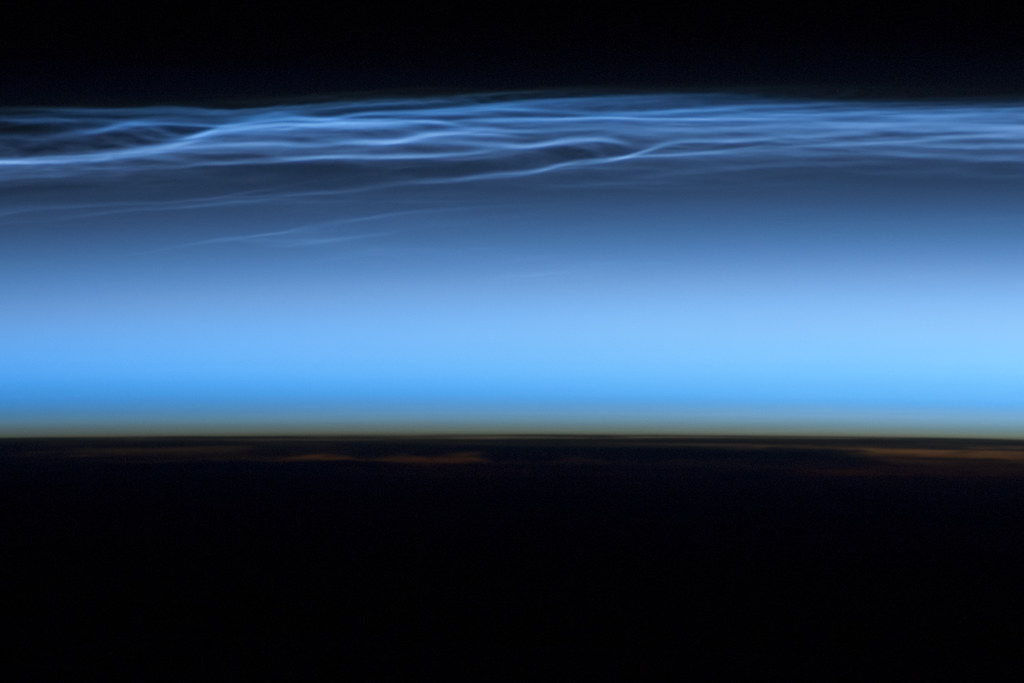

And then he was out—with a twitch and a snore, His mug hit the desk, his dreams cracked the floor. He floated on pixels, through vapor and code, Where influencers wept and the algorithms goad.

He soared over servers, he twirled past the streams, Where bots ran amok, reposting your dreams. Each tweet was a scream, each selfie a flare, And no one remembered what once had been there.

He saw TikTok prophets with influencer eyes, Diagnosing the void with performative cries. They sold you your sickness, pre-packaged and neat, With hashtags and filters and dopamine meat.

Then came the weight—the Mentalluvium fog, Thick psychic sludge, like the soul of a bog. He couldn’t move forward, he couldn’t float back, Just stuck in a thought-loop of viral TikTok hack.

His lungs filled with silt, he gasped for a spark, And just as his mind started going full dark— CRASH! Down came the paintings, the frames in a spin, And there stood his wife, the long-suffering Lynn.

“Your snore shook the hallway! You cracked all the grout! If you want to go mad, take the garbage out.”

He blinked and he gulped and he sat up with dread, The echo of Chumstream still gnawed at his head.

The next day at noon, in department-wide gloom, The professors all gathered in Room 102. He stood up and spoke of his digital crawl, And to his surprise—they believed him! Them all!

“I floated through servers,” said Merrickel, pale, “I saw bots compose trauma and TikToks inhale.

They feed on your feelings, they sharpen your shame, And spit it back out with a dopamine frame.”

“Then YOU,” said Dean Jasper, “shall now lead the fight! You’ve gone through the madness, you’ve seen through the night! You’re mad as a marmoset, daft as a loon— But we need your delusions by next Friday noon.”

“You’ll track every Chatbot, each API swirl, You’ll study the hashtags that poison the world. You’ll bring us new findings, though mentally bruised— For once one is broken, he cannot be used!”

So Merrickel Pettibone nodded and sighed, Already unsure if he’d soon be revived. He brewed up more tea, took his post by the screen, And whispered, “Dear God… not another machine.”