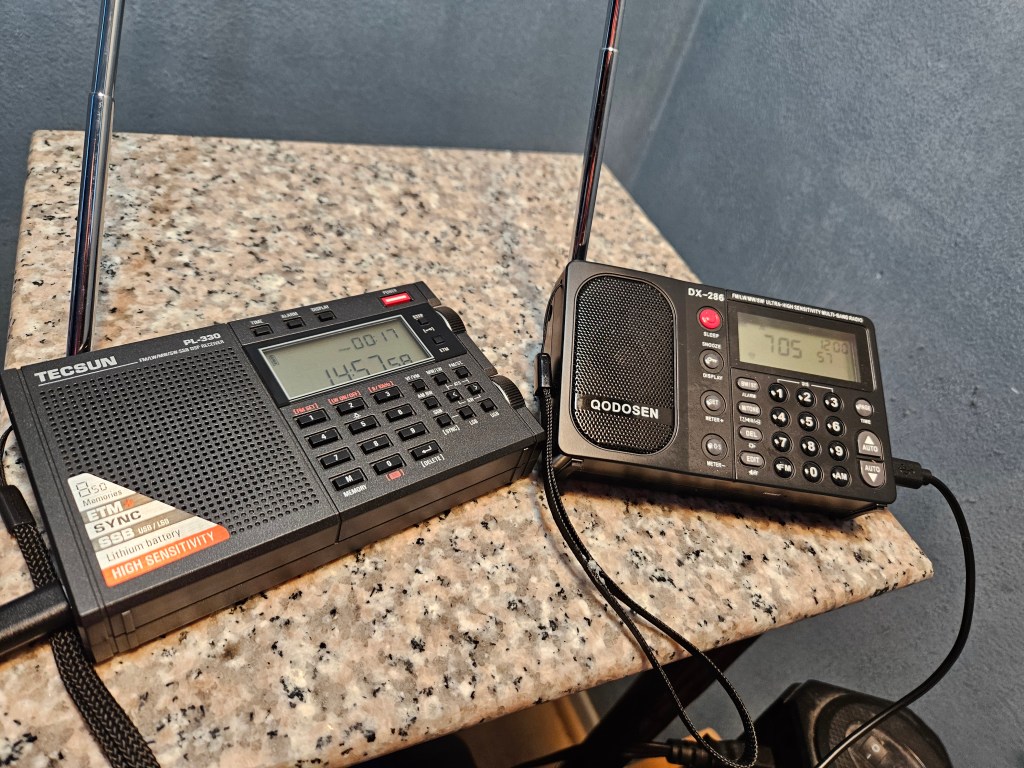

The following is from my now defunct Herculodge blog. I realized when I did radio testing again in 2025 that RFI (radio frequency interference) is a far greater challenge than it was in 2008. I need to play my radios on batteries, not AC adapters, and keep them away from walls, which is a shame because I really want the Sangean HDR-19, a wall adapter-only radio, which has gone up in price about $80 since even a couple of months ago.

Since the Los Angeles Fires tore through Southern California in January 2025, I realized my household was embarrassingly underprepared for live news coverage. Streaming devices and smart speakers suddenly felt flimsy when the sky turns orange. I needed something sturdier, more reliable—like a good, old-fashioned radio.

Enter Sangean, a brand I trusted a decade ago. I fondly remembered their radios delivering a warm, bass-heavy sound—pleasant, if not exactly hi-fi. My ancient PR-D4 still hums along in the garage, proof that Sangean builds workhorses. So, naturally, I picked up their new DSP-chip PR-D12, curious to see how it stacked up against its analog ancestor.

The verdict? The D12 is brighter and more balanced than the D4, though the warmth I loved has cooled a bit. FM reception is a mixed bag. From Torrance, Pasadena’s 89.3 comes in strong with three bars and crystal clarity on the D12. On the D4? Same signal strength but with a thin veil of static, unless I awkwardly angle the antenna like I’m searching for alien life.

But then things get weird. 91.5, my go-to classical station, sings smoothly on the D4 but sputters on the D12—two weak bars and static, no matter how I threaten the antenna.

AM? Forget it. 640 AM is listenable but laced with floor noise on both radios. I twist and turn the radios to align the internal ferrite antennas like I’m cracking a safe, but the noise stays. Worse, AM talk radio voices sound like they’re broadcasting through a burlap sack. Long-term listening? Not a chance.

What the D12 does have going for it is user-friendliness. Four preset pages with five slots each make navigating stations painless—perfect for my wife, who refuses to wrestle with complex manuals that read like an SAT prep book. She’s happy with 89.3 and 89.9 blasting clear and loud, so the D12 earns its spot in the kitchen.

Still, I can’t shake the feeling I need something more commanding, like the soon-to-arrive Tecsun PL-990x. Maybe it’ll crack the code on AM audio bliss. Until then, the PR-D12 holds the line—solid, if not inspiring.

Moderate recommendation.

Update:

I told my fellow radio enthusiast friend Gary about how I could not listen to the AM sound on the PR-D12 or my PR-D4, and he expressed the same sentiment. He said the only AM he can listen to from his vast radio collection is his now defunct C.Crane CC Radio-SW, which is a clone of the Redsun RP-2100. This made me sad because many years ago I enjoyed listening to AM on my Redsun RP-2100, but I fried it when I put the wrong AC adapter in it. Getting good AM sound out of a radio is hard these days.

Second Update:

Three days after writing this review, I moved the PR-D12 to the garage where it sounds great on AM so I blame the kitchen, not the PR-D12.