The TV show Loudermilk is part sitcom, part group therapy, and part existential smackdown. Ron Livingston plays Sam Loudermilk, a grizzled music critic and recovering alcoholic with the face of a hungover basset hound and the social graces of a man allergic to kindness. He barrels through life offending everyone within a five-foot radius, insulting his fellow addicts with toxic flair. But beneath the wreckage lies a strange tenderness—a story not just about addiction, but about people trying to survive themselves.

Loudermilk lives in a halfway house with a cast of human tire fires, and the comedy burns hot: irreverent, profane, and deeply affectionate. The show loves its damaged characters even as it roasts them alive. Naturally, I love Loudermilk. Love it like a convert. I’ve become a low-key evangelist, promoting it to anyone within earshot—including the assistant at my local watch shop.

This isn’t just any watch shop. I’ve been going there for 25 years. The Owner and the Assistant know me well—well enough to have witnessed the slow, expensive progression of my watch addiction, including the day I came in twice because the first bracelet adjustment “didn’t feel quite right.” It’s my barbershop. My confessional. My dopamine dispensary.

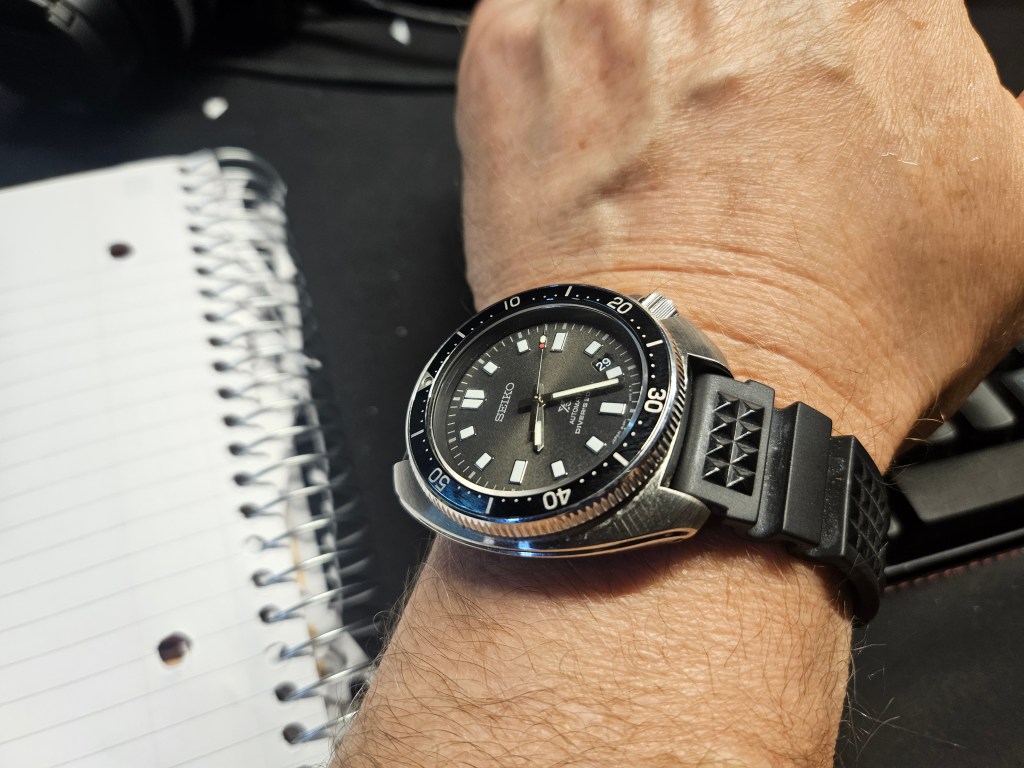

So one afternoon, I’m there getting a link removed from my Seiko diver and I bring up Loudermilk. I describe the show’s gallery of screwups—addicts clawing toward redemption by way of insults, setbacks, and semi-functional group hugs. The Assistant looks up from his tools and tells me something personal. He watches Loudermilk too. And he gets it. He’s thirteen days sober and goes to five meetings every morning—not because he’s a morning person. He tells me that in his culture, drinking into one’s eighties is just called “living.” But for him, it was a slow-motion self-immolation. Now, he’s trying to claw his way back.

Before I can respond, a woman with a chihuahua tucked under her arm chimes in from across the shop. She too is a Loudermilk fan. “What a shame it got canceled after three seasons,” she laments. The Assistant counters—there’s still hope for a revival. They argue lightly, both fully engaged, two strangers momentarily bonded over their shared love of a comedy about pain.

I say goodbye and step out of the store. That’s when it hits me.

I love Loudermilk because I see myself in it. I am an addict. Not just of watches, but of distraction, validation, control—whatever lets me delay the moment when I must confront the snarling voice inside me.

Writers like Steven Pressfield and Phil Stutz describe this inner saboteur with chilling clarity. Pressfield calls it Resistance, the destructive force that undermines your better self. Stutz names it Part X, the anti-you that wants you to abandon meaning and pursue comfort. Both insist the enemy must be fought daily.

And I know that voice. It’s lived in my head for decades.

Once, at an English Department Christmas party, a colleague called me “Captain Comedown.” I don’t remember what I said to earn the nickname, but it tracks. I’ve got that bleak edge, the voice that sees futility everywhere and calls it wisdom. But a better name than Captain Comedown comes from my childhood: Glum, the joyless little pessimist from The Adventures of Gulliver, whose go-to phrase was: “It will never work. We’ll never make it. We’re doomed.”

That’s my inner monologue. That’s my Resistance. That’s my Glum.

Every day I wrestle him. He tells me not to bother, not to try, not to hope. That joy is a scam and effort is for suckers. And some days, I believe him. Other days, I don’t. But the battle is constant. It doesn’t end. As Pressfield says, the dragon regenerates. My job is to keep swinging the sword.

And maybe, just maybe, buying a new watch is my way of telling Glum to shut up. It’s a shiny, ticking middle finger to despair. A symbolic declaration: The world still contains wonder. And precision. And brushed stainless steel.

But there must be cheaper ways to silence Glum. A walk. A song. A friend. A laugh. Even a half-hour with Loudermilk.

Because, irony of ironies, what addicts like me really want isn’t the next hit. It’s relief from the craving.