I’ve been both a watch enthusiast and a watch addict for over two decades—long enough to know the difference between a genuine passion and a performance art piece in a wrist-sized frame.

Some of my collecting history is noble. Some of it’s embarrassing. I’ve chased watches for the right reasons: fascination with engineering, aesthetics, a deeply personal sense of style. But I’ve also chased them for the wrong reasons: hero cosplay, status projection, and the sad, sweaty hope that someone—anyone—might think I was cool for wearing a submersible chunk of steel on my wrist.

Let’s call it what it is: I’ve bought watches to feel like a man. That instinct isn’t always authentic—it’s often a costume. And in the world of collecting, nothing poisons the well faster than performative masculinity dressed up as personal style.

So I started trying to pare things down. Simplify. Get to the core of what I actually like, and keep a small, personal collection that reflects who I am—not who I want Instagram to think I am.

Easier said than done.

Because in today’s world, “authenticity” has become just another algorithmic trend, another pantomime we perform for likes and approval. The word phony doesn’t even do justice to the industrial-strength fakery we’re marinating in. It’s beyond phony. It’s Olympic-level insincerity with corporate backing and PowerPoint slides.

We now live in a cultural ecosystem where people are so fake, their attempts at being authentic create new layers of fakery. It’s not just that they’re inauthentic—they’re meta-inauthentic. They study authenticity like it’s a language exam, and the harder they try to sound fluent, the more their accent bleeds through.

Take, for example, the great frauds of my TV-watching youth.

Eddie Haskell—Leave It to Beaver’s oily teenage suck-up—mastered the art of smiling at your mother while plotting your destruction behind the garage. He didn’t just imitate politeness; he weaponized it.

Then there was Dr. Smith from Lost in Space—the preening, verbose con man who brought zero medical skills to the spaceship but still managed to insult the robot with Shakespearean flair:

“You clumsy, colossal clod!”

“You insidious ignoramus!”

“You bubble-headed booby!”

Ironically, Dr. Smith’s insults turned me on to language itself. I owe the man my English degree. Which just proves: sometimes even a fraud can inspire something real.

Fast-forward to today’s most delicious case of catastrophic phoniness: the political operatives who realized they had alienated the male vote. After years of condescension, virtue signaling, and high-minded lectures, they finally realized men were tuning them out—if not outright recoiling.

So what did they do?

They flew to Half Moon Bay, checked into a luxury resort, and held a think tank retreat to rebrand masculinity. Picture it: Ivy League consultants in cashmere sweaters eating lobster rolls and sipping Pinot Noir while spitballing ways to reconnect with the “working man.” They treated young men like they were a rare species of jungle ape. Field notes were probably taken.

This level of cluelessness isn’t just tone-deaf—it’s operatic. If the writers of Succession pitched this as a storyline, HBO would tell them to tone it down for realism.

We need a name for this kind of oblivious, polished, self-defeating fakery. I call it Brotoxification: the act of rebranding yourself to appeal to men—but doing it with such manicured insincerity that you repel the very people you’re trying to win back.

I work with young men every day—college football players, ex-military students, guys grinding through school because life didn’t hand them a shortcut. They don’t want coddling. They want three things: structure, discipline, and real-life skills. The last thing they need is a smug consultant in designer sneakers telling them how to “be seen.”

And this circles back to watches.

A few ground rules for keeping your watch hobby clean:

1. Don’t overthink it.

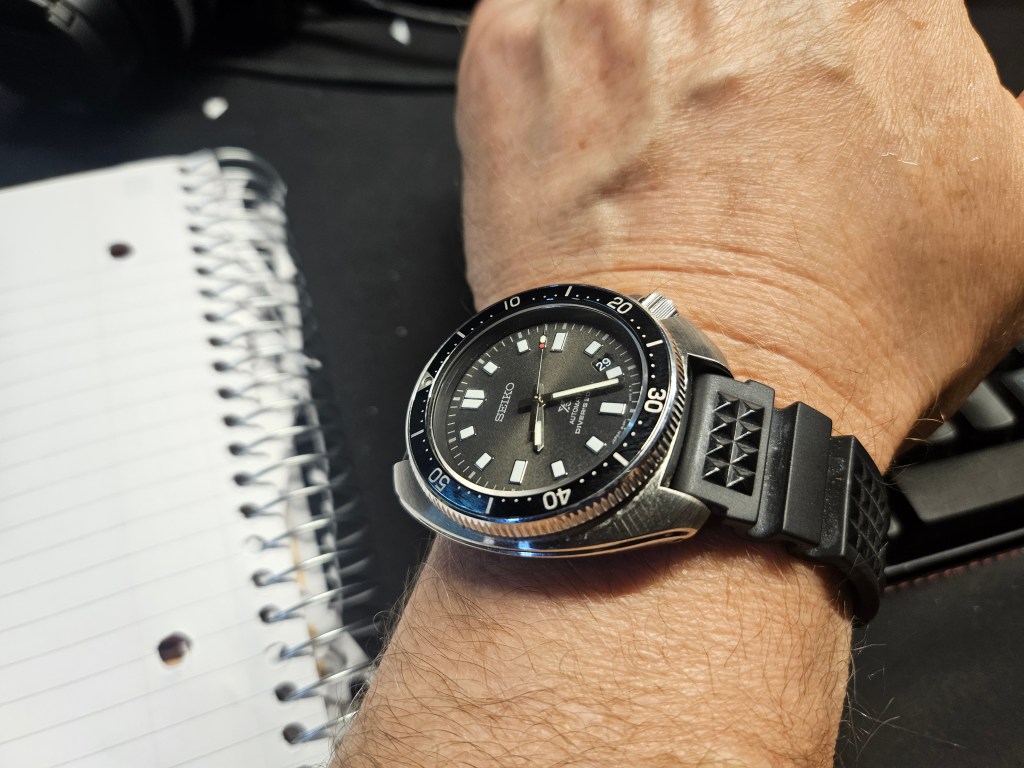

If a watch keeps whispering to you at 2 a.m., it probably belongs on your wrist. Trust your gut. You don’t need a panel of experts or a YouTube breakdown.

2. Never buy a watch because you think it’ll earn you applause.

If you’re trying to impress the crowd, the crowd will sniff out your desperation and laugh behind your back. Buying a “manly watch” to look tough is like buying cologne to smell rich. It doesn’t fool anyone.

3. You don’t need to be rich.

A $200 G-Shock Rangeman, worn with conviction, beats a $10,000 showpiece worn like a rented tux. Living within your means isn’t just practical—it’s masculine. It’s called integrity.

In the end, authenticity can’t be strategized. It’s not something you workshop in a resort ballroom between keynote speakers and complimentary wine pairings. It’s not a brand refresh. And it sure as hell isn’t something you can outsource to consultants.

Whether we’re talking about politics, masculinity, or watch collecting, the minute you start performing sincerity is the minute you’ve already lost it.

So do yourself a favor: Keep your hobby honest. Reject the Brotox. And wear your damn watch because you love it—not because you’re hoping someone else will.