FADE IN:

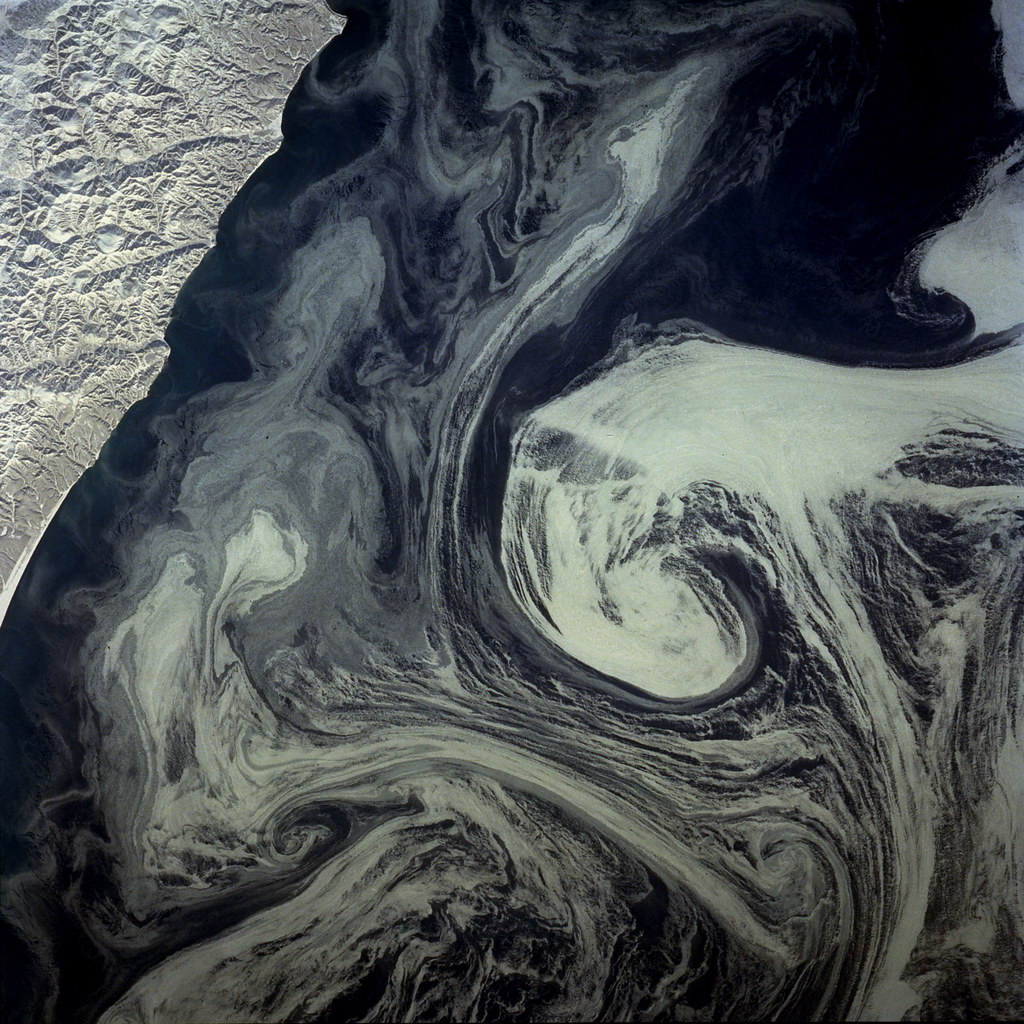

A road. It winds through the wastes like a serpent that forgot its own name. Cracked earth on either side. Fence posts like grave markers. Vultures in the sky, circling nothing in particular, just keeping warm. A man walks it. His boots are flayed open. His eyes are sunburned. His soul is a blister dragging itself behind him.

His name is Lyle. Or maybe Thomas. The script never says. Doesn’t matter. He’s every man who ever wrote a love letter in blood and mailed it into the void.

He is looking for her. She has no name, just a shape in the distance, a memory braided from perfume and last words. She left him. Maybe twice. Maybe more. He kept the door open. She never knocked.

The road has been long. Winding. Bleak. It led him through dead towns and ghost motels. Once he stayed in a place where the concierge was a buzzard and the minibar held only regret.

He speaks not. The road speaks for him. It says:

Every fool must follow something. You picked hope. Bad draw.

Flashbacks flicker: A woman, face soft as moonlight, eyes like unpaid debt. She tells him she’s leaving. He says he’ll wait. She laughs. That’s the last thing she gives him. Her laughter. Acid-bright and final.

Along the road he meets others—pilgrims of delusion.

One man rides a shopping cart filled with old love songs on cassette.

One woman sews wedding dresses for brides that never were.

One child sells maps to places that no longer exist.

They all walk. They all believe the road leads somewhere. It don’t.

Eventually, Lyle comes upon a house at the end of the road. It is the house. Her house. Or what’s left of it. The windows are boarded. The door is gone. Inside, just dust, a broken phonograph, and a bird trapped in the chimney, fluttering against the soot.

He kneels.

Not to pray. To listen.

There’s no music. No answer. Only wind. And the bird’s soft thump, thump, thump.

He lies down. The road curls around him like a noose.

FADE TO BLACK.

The final line scrolls in silence:

Love didn’t leave. It just stopped answering the door.