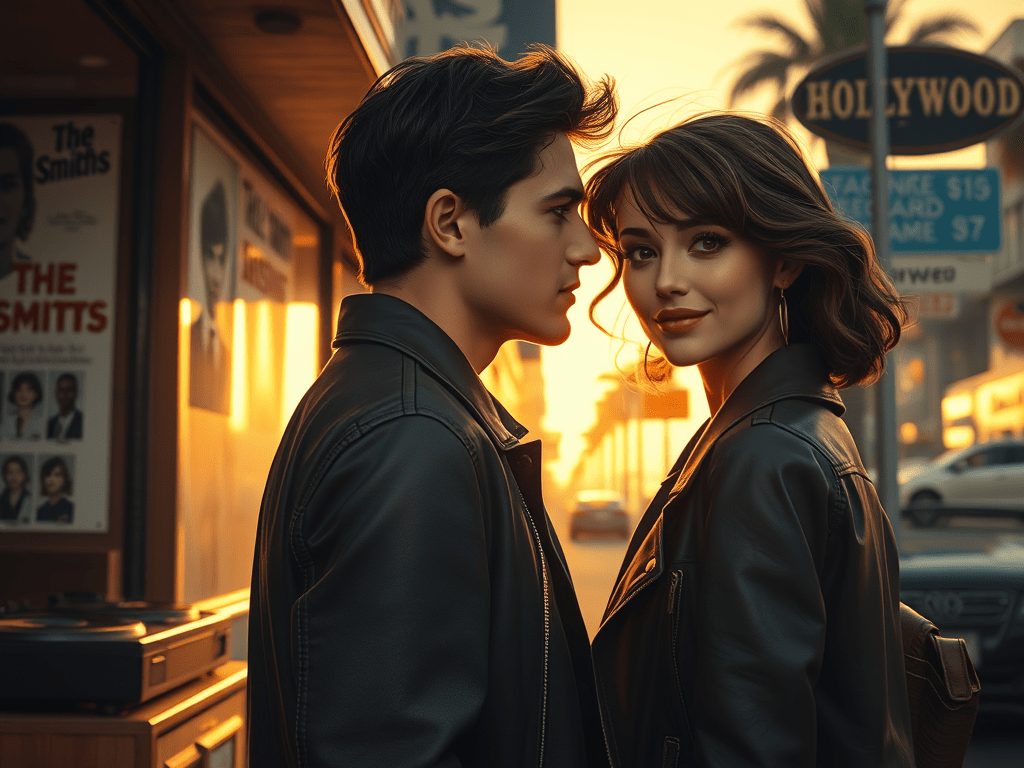

It was 1990, and there I was — strutting down Hollywood Boulevard with my girlfriend, a walking cliché in a secondhand leather jacket, pretending to be too jaded for the tourists but secretly hoping to be discovered by a roving talent scout. We ducked into some grim little shrine to adolescent misery, shopping for Smiths T-shirts and anything else that might broadcast our manufactured melancholy.

That’s when the store’s sound system offered up “Obscurity Knocks” by the Trash Can Sinatras — a song I was too full of myself to recognize as a direct warning shot.

At the time, I was a preening, would-be screenwriter and novelist, drunk on my own imaginary press clippings, convinced that obscurity was a fate reserved for lesser mortals. I didn’t realize that the bright, bittersweet melody washing over those racks of ironic despair was, in fact, my personal horoscope: You, sir, will toil unseen. You will remain a hidden draft in life’s file cabinet. And — shocking plot twist — it will not kill you.

Decades later, “Obscurity Knocks” still sits at the top of my all-time favorites list, not because it flatters ambition, but because it gently demolishes it.

It’s a hymn to living for the work itself, to making peace with invisibility, to resisting the cheap, sugary high of external validation.

It is one of those rare songs that manages to be both wistful and liberating at once — a graceful acceptance letter to a life lived outside the gravitational pull of fame. Far from being a bitter anthem of failure, it’s a clear-eyed celebration of choosing the harder, more honest road: living for one’s art rather than living off it.

At first listen, the jangly guitars and breezy melody almost betray the lyrical gravity beneath. The music is light, but the words carry the weight of a reckoning. The narrator stands at the border between youthful ambition and mature resignation, surveying the life he has actually lived versus the life he once imagined. And yet, there is no rage, no tantrum, no grasping for lost relevance. Instead, there is something far healthier and more beautiful: an elegy without self-pity, a conscious decision to stay faithful to the things that matter.

The song’s real bravery lies in its refusal to dress obscurity up as defeat. It suggests that real integrity means loving what you do even when the spotlight points elsewhere — when the record deals dry up, when the critics stop caring, when the audience forgets. In an era addicted to metrics — clicks, likes, views — “Obscurity Knocks” remains a defiant refusal to reduce one’s life to a scoreboard.

Mortality hums quietly underneath the entire track. It’s not explicit, but it’s there, felt in the weariness behind certain lines, the subtle wear and tear of a life measured not by trophies but by quieter, richer achievements: loyalty to craft, private joy, the bittersweet pleasure of simply carrying on. It accepts the inevitable fading without collapsing into nihilism.

There is longing, yes — the song aches with it — but it’s a clean, unsentimental kind of longing. It isn’t the longing for public adoration or manufactured relevance; it’s the deeper human longing to matter, to create something true before the clock runs out. In this way, “Obscurity Knocks” isn’t just about a music career. It’s about the universal experience of learning to live meaningfully in a world that will not give you a standing ovation for it.

The Trash Can Sinatras don’t rage against the dying of the light; they tip their hats to it, shrug, and keep playing. And in that shrug, that beautifully unvarnished acceptance, they find a kind of glory that fame could never offer.

Do the Trash Can Sinatras have a song more beautiful than “Obscurity Knocks”? Technically, yes — but only one, and finding it is like trying to locate the Holy Grail in a used CD bin. It’s a B-side called “My Mistake,” a painfully perfect little anthem about a young fool so drunk on love he trips over his own heart like it’s a barstool in a dark room.

It’s a song that captures, with ridiculous precision, the exquisite humiliation of thinking you’re the protagonist in a grand romance when you’re actually just a blip on someone else’s radar — a mistake you won’t stop making until life has finished sanding the delusions off your bones.

Postscript:

After writing this post, I felt compelled to listen to “Obscurity Knocks” on YouTube and someone asked in the comment section: “Any other songs like this?” I answered: “Yes, ‘My Finest Hour’ by The Sundays.”