It’s been a bruising semester. I’m teaching a class full of student-athletes—big personalities, bigger social circles. I like them; I even feel protective of them. But they’re driving me halfway to madness. They sit in tight cliques, chattering through lectures like it’s a locker room between drills. Every class, I play the same game of whack-a-murmur: redirect, refocus, remind them that the material matters for their essays. I promise them mercy—“just give me 30 minutes of focus before we watch the documentary or workshop your drafts”—but my voice competes with the hum of conversation and the holy glow of smartphones.

The phones are the true sirens of the classroom—scrolling, snapping, texting, attention atomized into pixels. Maybe it’s my fault for not collecting them in a basket like contraband. I thought I was teaching adults. I thought athletes, of all people, would bring discipline and drive. Instead, I’ve got a team that treats class like study hall with Wi-Fi. My essay topics that have created engagement in past semesters—like Jordan Peele’s Sunken Place—barely register. The irony: I’m showing them the metaphor for psychological paralysis, and half the room is literally sinking into their screens.

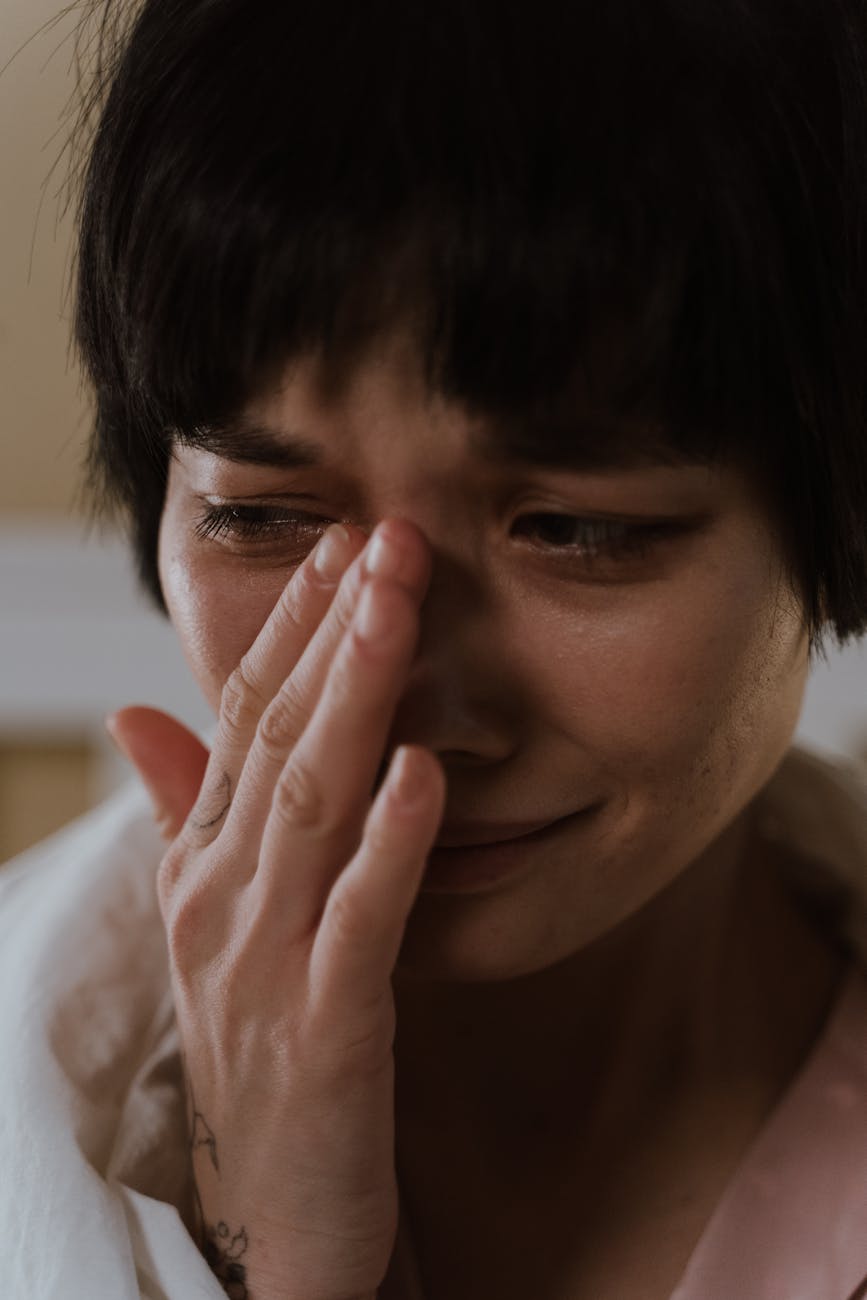

After thirty years of teaching, this is the hardest semester I’ve had. I kept telling myself, Five more weeks and the storm will pass. Next semester, you’ll have your groove back. Today I spoke with a colleague who teaches the same class to the general population—same disengagement, same cell phones, same glazed eyes. He added one more grim diagnosis: the rise of fragility. When he points out errors, missing citations, too much AI-speak, or low effort, students protest that his feedback “hurts their feelings.” They’re not defiant—they’re delicate. Consequences have become cruelty.

That word—consequences—haunted me as I walked to class. I thought about my own twin daughters at their highly rated high school, where late work flows freely, “self-esteem” trumps rigor, and parental complaints terrify administrators more than failing grades. It hit me: this isn’t an athlete problem—it’s a generational shift. The No Consequences Era has arrived. Students no longer fear failure; they resent it. And the tragedy isn’t that they can’t handle criticism—it’s that they’ve never been forced to build the muscle for it.