In the blistering summer of 1971, when I was nine years old and fully convinced that the universe owed me something dazzling—preferably in Technicolor—my family and four others staked out a patch of wilderness on Mount Shasta. For two solid weeks, we rough-camped our way through a supposedly idyllic escape: fishing, water-skiing, dodging hornets, and marinating under the sun to a soundtrack of The Doors, Paul McCartney, Carole King, and Three Dog Night blasting from a battery-powered boom box the size of a microwave. It should have been paradise. It had all the ingredients. But for me, something essential was missing—specifically, a split-level ranch house with shag carpeting and Alice the maid humming in the kitchen.

One morning, while the other families performed their pioneer cosplay—flipping pancakes and waxing poetic about fish guts—I was still swaddled in my sleeping bag, experiencing what I can only describe as a divine transmission. In my dream, I had been plucked from obscurity and absorbed into The Brady Bunch. Not as a guest star. As family. It all unfolded on a sun-drenched San Francisco street corner, beside a cable car gleaming like a chariot of middle-class destiny. Mike, Carol, Greg, Marcia, Peter, Jan, Bobby, and Cindy—smiling like cult recruiters in polyester—welcomed me into the fold. It was done. The adoption papers had been processed. I was now officially Brady-adjacent.

The implications were staggering. Would I get my own room in this avocado-hued utopia? Or would I bunk with Greg and be forced to suffer his groovy condescension? Would I be featured in a Very Special Episode? Just as these critical logistics were about to be resolved, reality sucker-punched me. Mark and Tosh—my alleged friends—yanked me out of my dream state, barking something about going fishing. Fishing? I had just been inducted into America’s Most Wholesome Family, and now I was supposed to sit on a rotting log and bait a hook like some peasant?

I sulked through the day like a dethroned sitcom prince, scowling at everything from the trees to the trout. But what could I say? That I’d just been psychically ejected from a pastel-tinted suburban heaven? That I was mourning the loss of a pretend life more emotionally satisfying than my real one? Try explaining that to your father, a military man in tube socks and Tevas, who barked, “We’re living in the wild!” with the enthusiasm of someone allergic to introspection.

I didn’t want the wild. I wanted shag rugs and chore wheels. I wanted avocado-colored appliances and a staircase for dramatic entrances. I wanted to wake up in a house where even problems came with laugh tracks and gentle moral resolutions. But instead, I got mosquitoes, hornet attacks, and the cold reality that I was not, in fact, a Brady.

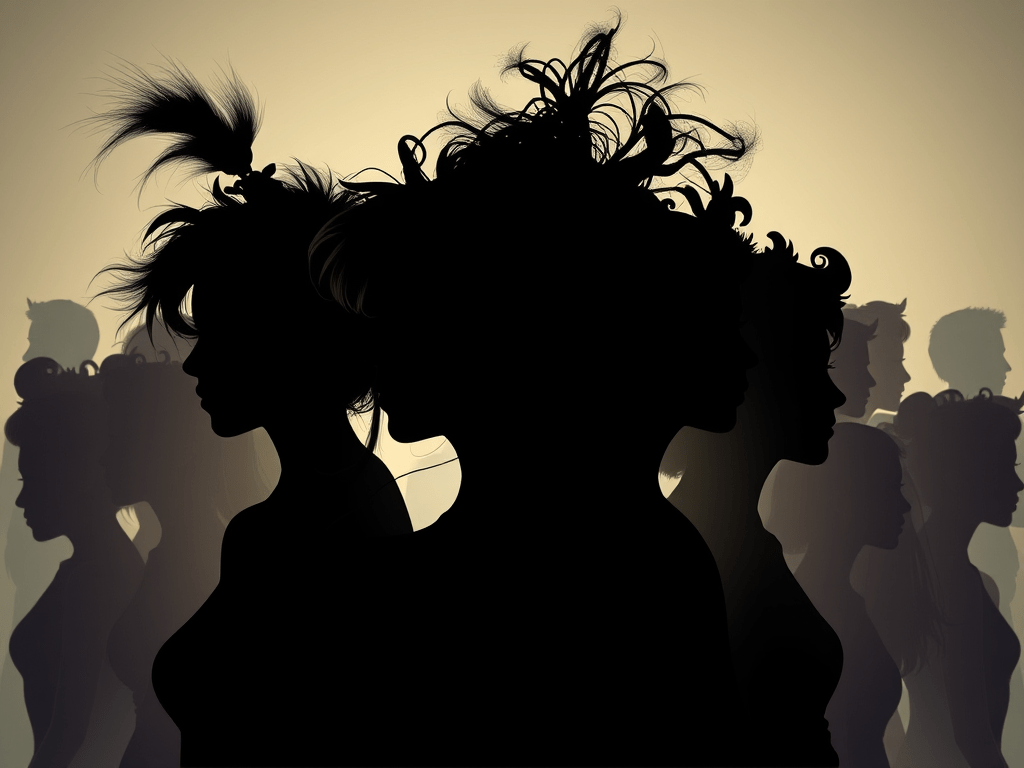

But here’s the kicker: I wasn’t alone in this delusion. In the pre-digital 1970s, The Brady Bunch was the mother of all FOMO engines. Long before Instagram filtered our envy, Sherwood Schwartz’s sitcom utopia beamed into our wood-paneled living rooms and convinced millions of us that we’d been born into the wrong family. It wasn’t just television—it was aspirational family porn.

And the letters poured in. Hundreds, maybe thousands, from children in broken homes offering to renounce their worldly possessions if they could just live under that sacred A-frame roof with Carol and Mike. The Bradys weren’t just a TV family—they were a mirage of emotional security, mass-produced and broadcast at 7 p.m., five nights a week. Sherwood Schwartz accidentally started a cult, and every kid in America wanted in.

What no one knew, of course, was that the real Brady kids were unraveling offscreen. Drugs, affairs, backstabbing—your standard-issue Hollywood breakdown, now available in bell-bottoms. While we were fantasizing about solving our adolescent angst in a 30-minute morality play, the actors playing our surrogate siblings were spiraling. Turns out, the squeaky-clean family fantasy was just that: a brilliantly lit lie.

And yet, we clung to it. Why? Because once you’ve tasted Brady-level manufactured bliss, the real world—be it Mount Shasta or your own dysfunctional dining room—feels insufficient. That’s the cruel brilliance of FOMO: it convinces you there’s a better life just out of frame. And if you don’t have it, something must be wrong with you.

To this day, I still occasionally dream I’m floating inside that iconic title sequence, my face glowing in one of the boxes, beaming down at Bobby or Jan as if everything in the world had finally clicked. In that dream, I am forever young, forever welcome, and forever untouched by the grinding disappointments of real life. I am, for thirty glorious seconds, a Brady.

And then I wake up. And it’s just me, my real family, and whatever wildness we’ve decided to romanticize that year.