Everyone has an origin story. You are no exception. Yours begins with your father. Without your father’s sheer audacity and competitive determination, you wouldn’t even be here today. Long before you were a glint in his eye, your father was locked in a battle of epic proportions—an all-out, no-holds-barred contest for the affections of your eighteen-year-old mother. And this wasn’t just any competition. His rival? None other than John Shalikashvili, future United States General and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Their battlefield? The smoky, beer-soaked bar scene of Anchorage, where the stakes were higher than a highball glass during happy hour.

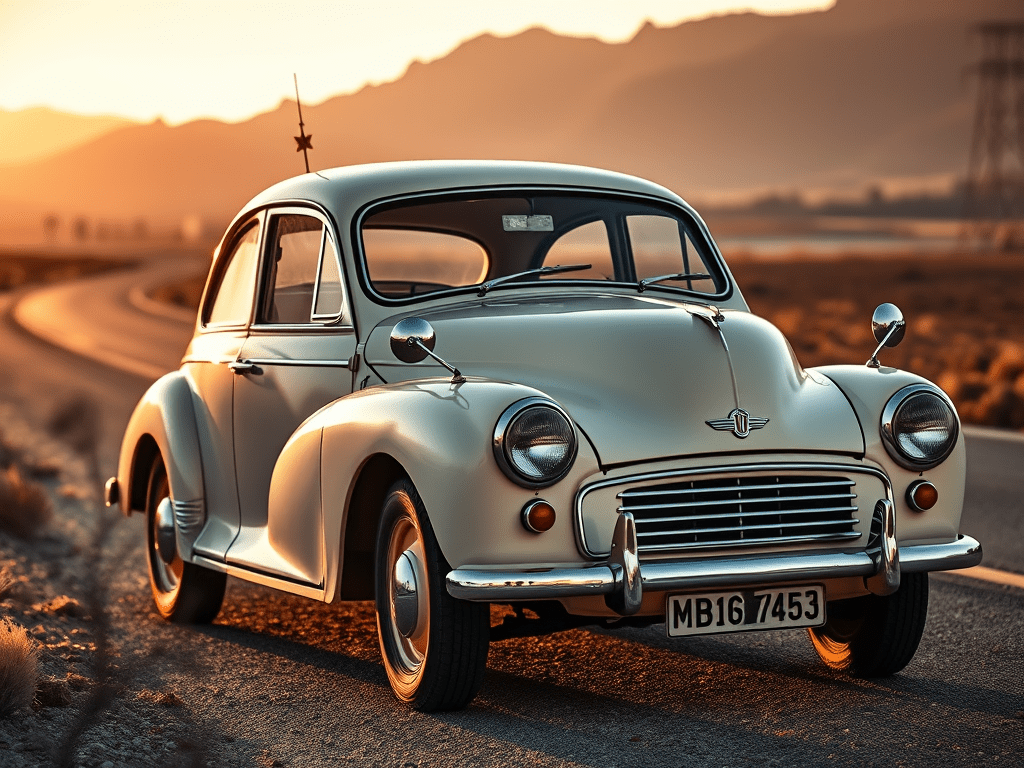

Their duel for your future mother’s heart took a brief Christmas ceasefire when Shalikashvili retreated to his tactical command center in Peoria, Illinois, while your father returned to Hollywood, Florida, to soak up some sunshine and plot his next move. But as he lounged by the pool, your father realized that victory in this romantic Cold War required swift and decisive action. So he cut his vacation short, crammed himself into a cream-colored 1959 Morris Minor—a vehicle that looked like it had been assembled from the Island of Misfit Toys, complete with a coat hanger for an antenna and door handles barely clinging on by the grace of duct tape—and embarked on the most high-stakes road trip of the 20th century.

Halfway through this odyssey, the car’s fuel filter decided to go on strike, leaving your father stranded in the middle of nowhere. When the local auto parts store couldn’t supply a replacement, your father—who would later perform engineering miracles at IBM—pulled off a MacGyver-level feat of mechanical wizardry. Armed with nothing but a prophylactic and a paperclip, he fashioned a makeshift fuel filter that was equal parts creative desperation and mechanical blasphemy. This duct-taped miracle kept the fuel pump from either flooding the engine or abandoning ship entirely, depending on its mood.

Driven by the urgency of love and the fear of losing ground to Shalikashvili’s brass-polished charm, your father powered through the journey, ignoring his growling stomach like a man possessed. Subsisting on loaves of bread devoured like a feral squirrel, he soldiered on, skipping meals because, who needs food when you’re racing against the clock to prevent a military coup over your future wife?

After a ferry ride that probably felt like crossing the River Styx, your father finally arrived in Anchorage, a full forty-eight hours before Shalikashvili could swoop in with his military swagger and irresistible authority. Nine months later, you were born, the ultimate trophy in this love-struck arms race.

Even before you took your first breath, your father’s victory over Shalikashvili imparted some crucial life lessons: The competition is fierce, and life is a zero-sum game where you’re either a winner or a nobody. To survive, you must find a competitive edge, and if you ever get complacent, rest assured, someone will move in on your turf faster than you can say “ranked second.”

As a teenage bodybuilder obsessed with becoming Mr. Universe, opening a gym in the Bahamas, and silencing your critics, you often thought about bodybuilding great Ken Waller stealing Mike Katz’s shirt before a competition in the movie Pumping Iron. Something as trivial as a missing shirt could send your opponent into a tailspin, disrupt his focus, and rattle his confidence like a cheap shaker bottle. Like Mr. Universe Ken Waller, your father taught you that power is a road paved with relentless cunning, ruthless strategy, and a healthy dose of underhanded shenanigans.

But underneath the shenanigans and Machiavellian flair, your father taught you one core truth: sweat more than everyone else. Out-hustle, out-grind, outlast. In his gospel, sweat wasn’t just effort—it was currency. The person who left the biggest puddle won.