If you only watch one episode of Black Mirror, let it be Joan Is Awful—especially if you have a low tolerance for tech-dystopian fever dreams involving eye-implants, social scores, or digital consciousness uploaded to bees. This one doesn’t take place in a dark tomorrow—it’s about the pathology of right now. It skewers the Curated Era we already live in, where selfhood has been gamified, privacy is casually torched, and we’re all trapped in the compulsion to turn our lives into content—often awful, but clickable content.

Joan, the title character, is painfully ordinary: a mid-level tech worker trying to swap out one man (her manic ex) for another (her milquetoast fiancé) and coast into a life of retail therapy and artisanal beverages. Her existence—Instagrammable, calibrated, aggressively average—is exactly the kind of raw material the in-universe Netflix clone Streamberry is looking for. They turn her life into a show called “Joan Is Awful,” starring a CGI deepfake Salma Hayek version of Joan, who reenacts her life with heightened melodrama and algorithmically-optimized awfulness.

This isn’t speculative fiction. It’s just fiction.

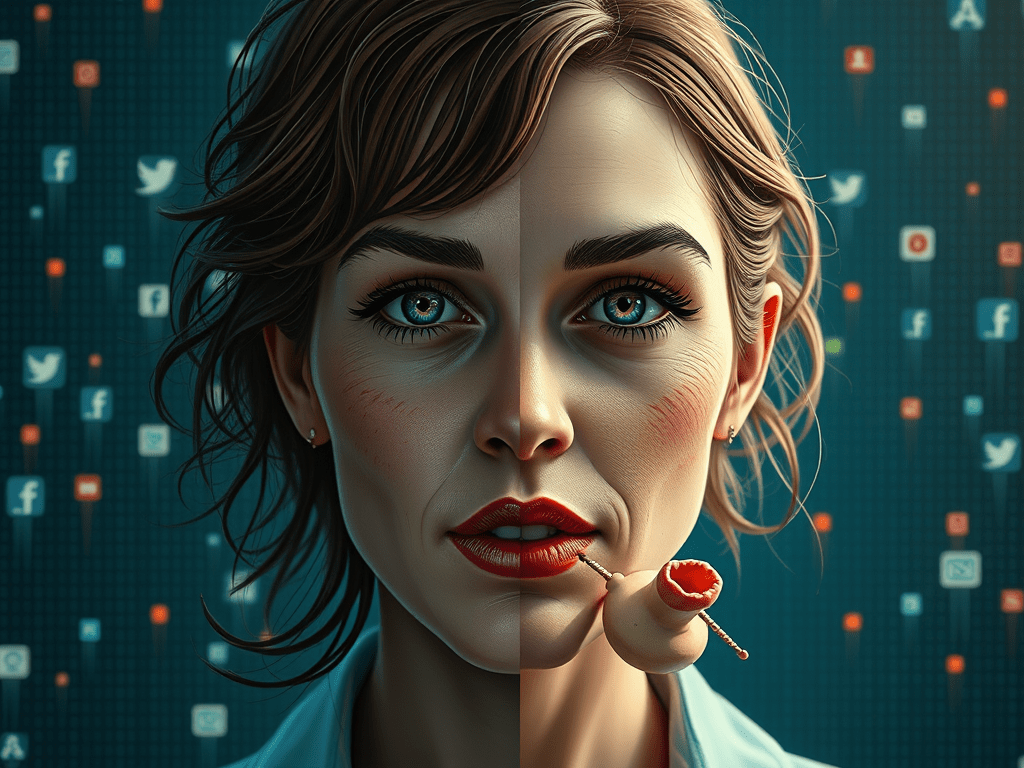

Streamberry’s vision of a personalized show for everyone—one that amplifies your worst traits and pushes them out for mass consumption—is barely an exaggeration of what Instagram, TikTok, and YouTube are already doing. We’ve all become our own showrunners, stylists, and publicists. Every TikTok tantrum and curated dinner plate is an audition for relevance, and the platforms reward us for veering into the grotesque. The more unhinged you become, the more “engagement” you earn.

“Joan Is Awful” works both as a laugh-out-loud satire and as a metaphysical gut-punch. It invites us to contemplate the slippery nature of selfhood under surveillance capitalism. At its core is the concept of “Fiction Level 1”: the dramatized version of Joan’s life generated by AI, crafted from data scraped from her phone, her apps, her browsing history. Joan doesn’t write the script. She doesn’t even get to protest. She’s just the original dataset—fodder for narrative extraction. Her real self is mined, exaggerated, and repackaged for mass appeal.

Sound familiar?

In the real world, we all star in our own low-budget version of “Joan Is Awful,” plastered across social media feeds. These platforms don’t need deepfakes. We willingly create them, editing ourselves into marketable parodies. We offer up a polished persona while our actual selves starve for air—authenticity traded for audience, spontaneity traded for algorithmic approval.

You can enjoy “Joan Is Awful” as slick satire or you can unpack its metafictional mind games—it rewards both approaches. Either way, it’s easily one of Black Mirror’s top-tier episodes, alongside “Nosedive,” “Rachel, Jack and Ashley Too,” and “Smithereens.” It’s not science fiction. It’s just a very well-lit mirror.