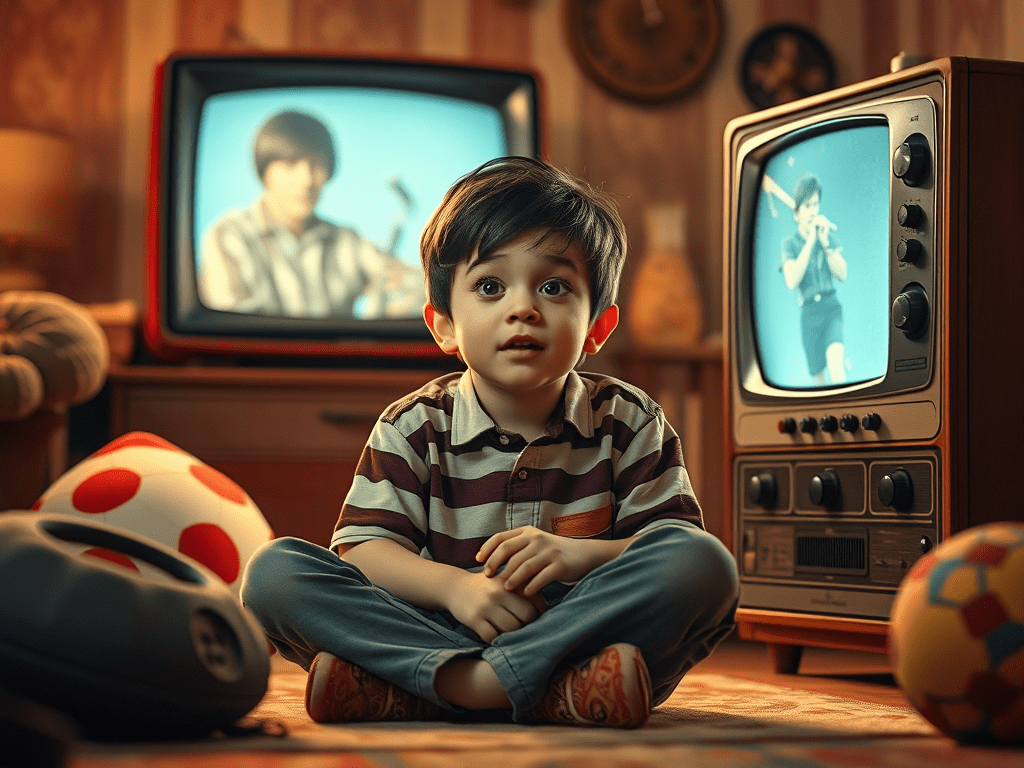

On the night of October 16, 1967—just twelve days shy of my sixth birthday—the universe shoved my head in the toilet and flushed. I could hear the sound of childhood innocence circling the drain. Up to that moment, I was a full-time subscriber to the gospel of positive thinking. Life was fair. Good guys won. If you tried hard and smiled big, the world smiled back. Norman Vincent Peale had basically written the owner’s manual for my inner world.

That illusion shattered during an episode of The Monkees.

The episode was called “I Was a 99-lb. Weakling,” and I had parked myself cross-legged in front of the TV, popcorn in lap, expecting hijinks and musical numbers. Instead, I got a masterclass in betrayal and the savage laws of ironic detachment. My hero, Micky Dolenz—the clumsy, lovable soul who made failure seem like a jazz solo—was brutally outmuscled by Bulk, a flexing monolith of a man played by real-life Mr. Universe, Dave Draper. Bulk didn’t walk—he heaved himself through scenes, a sculpted rebuke to every noodle-armed dreamer in America.

And right on cue, Brenda—the beachside Aphrodite with hair that shimmered like optimism—dropped Micky like a sack of kittens for Bulk, never once looking back.

This wasn’t just sitcom plot; this was emotional sabotage. I watched, frozen, as Micky enrolled in “Weaklings Anonymous,” embarking on a training montage so grotesquely absurd it veered into tragedy. He lifted dumbbells the size of moon rocks. He drank something called fermented goat milk curd, a substance that looked like it had been skimmed off a medieval wound. He even sold his drum set—his very soul—to chase the delusion that muscles would win her back.

And then came the twist.

Just as Micky completed his protein-fueled crucible, Brenda changed her mind. She didn’t want Bulk anymore. She wanted a skinny guy reading Remembrance of Things Past. A man whose pecs had clearly never met resistance training, but whose inner life pulsed with French ennui. The entire narrative pirouetted into absurdity, and I watched my belief system crack like a snow globe under a tire.

That’s when I first met irony.

Not the schoolyard kind where someone says “nice shirt” and means the opposite—but the bone-deep realization that the universe isn’t fair, that effort doesn’t guarantee reward, and that life doesn’t play by the moral arithmetic taught in Saturday morning cartoons.

It was that night I realized muscles weren’t the secret to power—language was. Not curls, not crunches, but craft. Syntax. Prose so sharp it could reroute the affections of beach goddesses and turn the tide of stories. That was the moment my childish faith in “try hard and you’ll win” collapsed, and in its place rose a darker, more potent creed: the pen is mightier not just than the sword, but than the bench press.

That night, my writing life began—not with celebration, but with betrayal. A glittering lesson delivered in the cruel, mocking tone only irony can wield. And though it hurt, I never forgot it. Because the truth is: irony teaches faster than optimism. And it remembers longer, too.

Leave a comment