In Lessons for Living, Phil Stutz recounts his refusal to prescribe Prozac to a patient. The patient wanted the pill as he wanted everything else—romance, fame, applause, alcohol: all shortcuts to happiness. Stutz wasn’t buying it. He writes:

“Believing that things outside you will make you happy is a false hope. The Greeks considered it the ‘doubtful gift from the gods.’ In reality, there can only be two outcomes. Either the hoped-for thing does not happen, or it does and its effect quickly wears off. Either way, you are worse off than before because you have trained yourself to fixate on outer results.”

When the outer world filters through imagination, it becomes a chimera. We don’t pursue things for what they are, but for what we fantasize they’ll be. I feel this pull myself: I’m nearly sixty-four, inching toward retirement, and browsing real estate in Orlando—dreaming of a second life in a faux-tropical paradise. A $600K “mansion” with a community pool, an hour from the beach, safe from hurricanes (mostly). Yet what I imagine as paradise may in fact be a barcalounger-sized sarcophagus—3,000 square feet of embalmed leisure.

Stutz warns against such chimeras. They must be replaced by action—behavior that connects us to our true nature: the spiritual self. He writes:

“We are spiritual beings and can be emotionally healthy only when we are in touch with a higher world. We need higher forces just as we need air. This is not an abstract philosophy, it is a description of our nature.”

But here’s the rub: staying in touch with higher forces requires constant work, and it’s in our nature to avoid work. Life, then, is a perpetual battle with ourselves. Stutz’s description amounts to the purpose of religion: the angel conquering the demon. Yet in our therapeutic age—where religion is dismissed as a fairy tale—misalignment between spiritual thirst and materialist fixation manifests as depression. Conventional psychiatry treats depression with drugs. Stutz reframes it as a teacher, a reminder that the answer is spiritual life:

“This awareness is the first step in overcoming depression.”

His point calls to mind Katie Herzog’s mention of Laura Delano’s memoir Unshrunk, a story of misdiagnosis and drug therapy that deepened rather than cured suffering. It also echoes Philip Rieff’s famous distinction in The Triumph of the Therapeutic:

“Religious man was born to be saved; psychological man is born to be pleased.”

Stutz insists that pleasing ourselves with material trinkets is a false and destructive path. Real responsibility means behaving in ways that connect us with our spiritual core. Judaism frames this as God meeting us halfway; Pauline Christianity insists we are helpless, depraved, and must be remade entirely. I’d be curious to know where Stutz lands on this divide.

Either way, his therapy unsettles his patients. A man clinging to Prozac, money, and fame stares at Stutz as though he’s lost his mind. Why? Because society has brainwashed us into believing happiness comes from external outcomes.

So what’s the alternative? Relentless self-monitoring. Stutz writes:

“Taking responsibility for how you feel isn’t an intellectual decision. It requires monitoring yourself every moment. This is the most freeing thing a person can do, but also the most tedious. Your connection to the higher world must be won in a series of small moments. Each time you become demoralized, depressed, or inert, you must counteract it right then.”

This isn’t entirely secular advice. Proverbs tells us to hang wisdom notes around our necks. Today, that might be post-its urging us to choose virtue over distraction. Still, Paul’s lament in Romans—that his darker nature sabotages his noblest intentions—remains apt. If Paul were not a Christian convert, would he be able to successfully use Stutz’s tools to connect with his Higher Powers, or would his dark side undermine the mission over and over?

Stutz’s counsel is pragmatic: notice when you sever your connection to the higher world, and fight back. If I’m meant to write or practice piano but instead scroll the Internet’s dopamine-drenched rabbit holes, that’s the moment to act. As Stutz puts it:

“If your habit is to look outside yourself for stimulation or validation, then each time you fail to get it, you’ll become depressed. But if you assume inner responsibility for your own mood and take action to connect yourself to higher forces at the moment you feel yourself going deep into a hole, you will develop habits that put you on a new level of energy and aliveness.”

In darkness, we don’t have to surrender. The “inner tools” give us armor. Stutz writes:

“The only way to achieve this confidence is to take a tool and actually experience how it works. Only then will you be willing to do what is required, which is to use it over and over, sometimes many times within one day.”

One such tool is “transmutational motivation.” The exercise: picture yourself demoralized after indulging temptation. Then imagine a higher power above you. Visualize yourself taking forward motion—meditation, writing, exercise—and rising into “the jet stream.” Stutz writes:

“Now you are going to fly straight up into this picture by feeling yourself take action and imagining this feeling causes you to ascend. Tell yourself that nothing else matters except taking the action. As you feel yourself rise, sense the world around you falls away. There is nothing except the action itself. Rise high enough to enter the picture. Once inside, tell yourself that you have a purpose. You will feel a powerful energy. To end the exercise, open your eyes and tell yourself that you are determined to take the pictured action. This time you will feel the picture above you pull you effortlessly up into itself. You will feel expanded and energized.”

With practice, the ritual takes fifteen seconds. Done daily, it rewires despair into life force.

But is this just Part X renamed? Steven Pressfield’s Resistance? Pauline sin? Or all of the above? Does Christianity accuse Stutz of diluting prayer into self-help? Do secularists argue his method is religion without the dogma? The questions multiply.

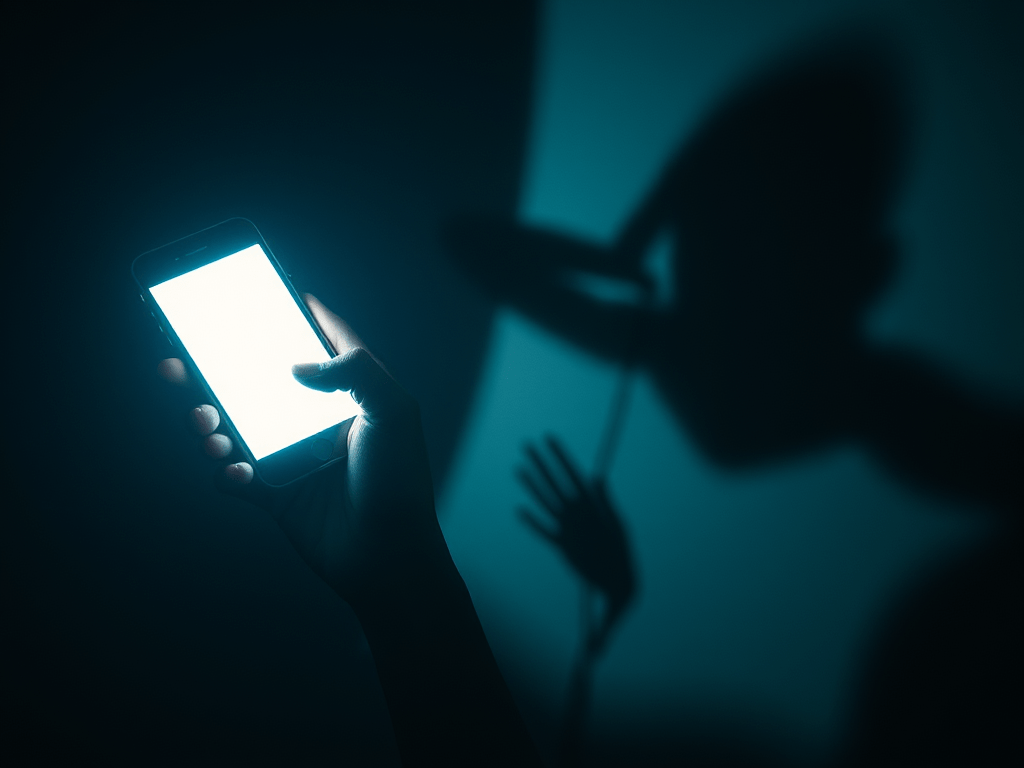

Anna Lembke’s Dopamine Nation frames it as neuroscience. Charles Duhigg’s The Power of Habit frames it as cognitive-behavioral reprogramming. Stutz straddles both: science and soul. And looming above it all is the Internet—the Great Temptor of our age. A bottomless pit of pornography, consumerism, and status-chasing, piped directly into our dopamine circuits.

And here’s the meta-question: what’s the point of rewiring your habits without a greater frame of meaning? Is Stutz peddling spirituality without religion—or is he smuggling in a stripped-down religion we secretly crave? Would Sam Harris nod approvingly at this secularized toolkit? Or would Dale Allison, the careful Christian scholar, recoil and insist that while Stutz offers clever strategies for habit change, he misses the essence of true spirituality—the self-giving sacrifice patterned after Christ in Philippians?

Unanswered questions aside, Stutz’s message is stark: life is high-stakes. We are fighting, every day, between dark and light forces. We don’t just change habits to “optimize” our brains. We change them to keep our souls alive.