One warm California afternoon in the spring of 1973, after sixth-grade classes had spit us out and the school bus rumbled off, leaving us at the corner of Crow Canyon Road, my friends and I followed our sacred ritual: a pilgrimage across the street to 7-Eleven to score a Slurpee before facing the long, punishing climb up Greenridge Road. Inside that air-conditioned oasis of fluorescent lights and sugar, “Brandy (You’re a Fine Girl)” crackled from the tinny store radio, its chorus bouncing off the racks of bubble gum and beef jerky.

That’s when the Horsefault sisters walked in like a blonde tornado.

They were tall, freckled, and wild—sunburned Valkyries with tangled golden hair, mischievous blue eyes, and the kind of high cheekbones that made me momentarily forget I was twelve. One was an eighth grader; the other, a high school sophomore, already possessing the dangerous confidence of someone who knew she could upend your world with a glance. They lived on a rundown farmhouse just behind the store, surrounded by fields and mystery.

“Wanna see a rabbit in a cage?” the younger one asked, her grin too wide to be trusted.

I didn’t give two figs about rabbits, but the sisters had figures that awakened my dim childhood memories of Barbara Eden in I Dream of Jeannie—my first crush and the gold standard of unattainable beauty. So naturally, I replied, “Absolutely.”

We left 7-Eleven, the door jingling behind us, and crossed into a sun-bleached field dotted with dry horse dung, the air sharp with the tang of manure and wild grass. A dirt trail wound past scrubby bushes and led to the edge of their sagging farmhouse. Behind a thicket of weeds sat a large iron cage with a rusted chain hanging off the latch. The door yawned slightly open like the maw of a trap.

I peered inside. No rabbit. Just hay, a few feathers, and a faint smell of old alfalfa and chicken droppings. Before I could even register the absence of the promised bunny, the sisters attacked—howling with glee like feral imps. One grabbed my arms, the other lunged for my legs, and together they tried to wrestle me into the cage.

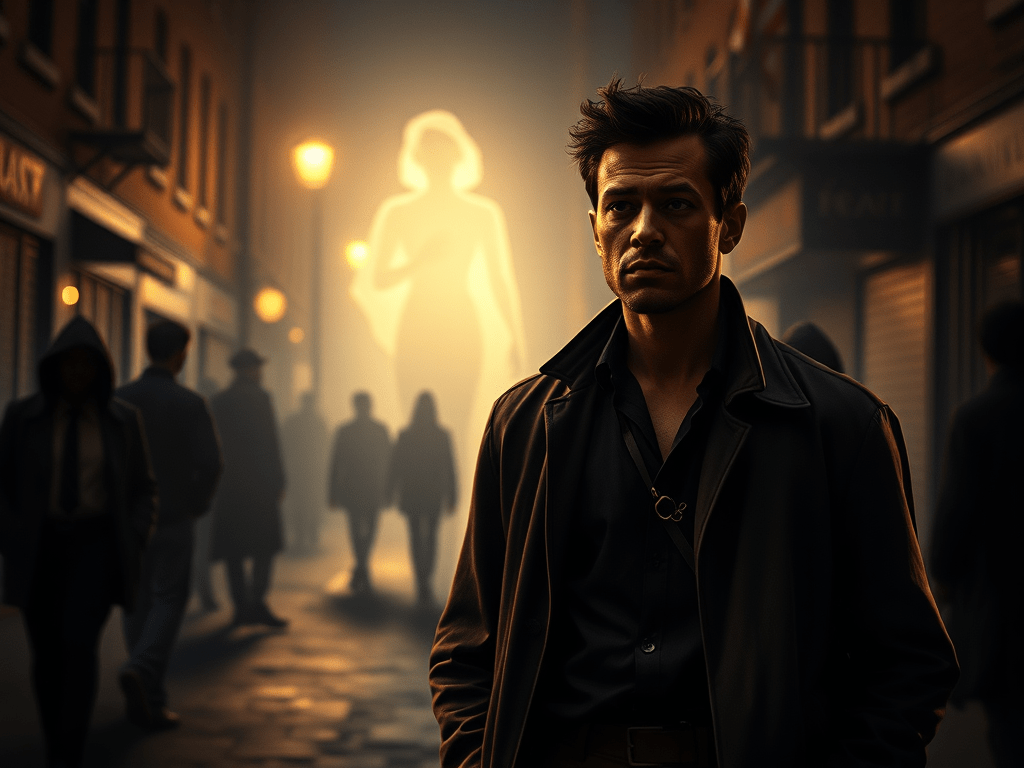

It was clear: I had been duped by a pair of rural sirens, not into love, but into captivity.

But they had underestimated me. I was stocky, wiry, and recently obsessed with Charles Atlas. I fought back with the desperation of a wrongfully accused man resisting a wrongful life sentence. We rolled in the tall grass, kicking up dust, hay, and chicken feathers as if auditioning for a Benny Hill episode shot on a farm. A nearby chicken coop exploded with chaos—panicked clucks and frantic wing flaps erupted like a poultry apocalypse.

The sisters, now sweaty and streaked with dirt, were panting from their failed coup. Realizing they didn’t have the brute strength to imprison me, they collapsed in giggles and defeat. I seized my chance and bolted—running like a fugitive through the meadow, Slurpee long forgotten, heart pounding like a kettle drum.

I got home, still breathless, still incensed by the attempted kidnapping, and turned on the TV to calm my frayed nerves. There she was: Barbara Eden, in her satin harem pants and cropped top, looking radiant and unbothered, stuck in her gilded bottle and waiting to be summoned. For the rest of the afternoon, I lay on the carpet in front of the television, sipping water from a mason jar and watching Jeannie coo and blink and call her master “darling.”

Unlike me, she never had to wrestle two hormonal farm girls behind a convenience store to escape a rabbit-less cage.