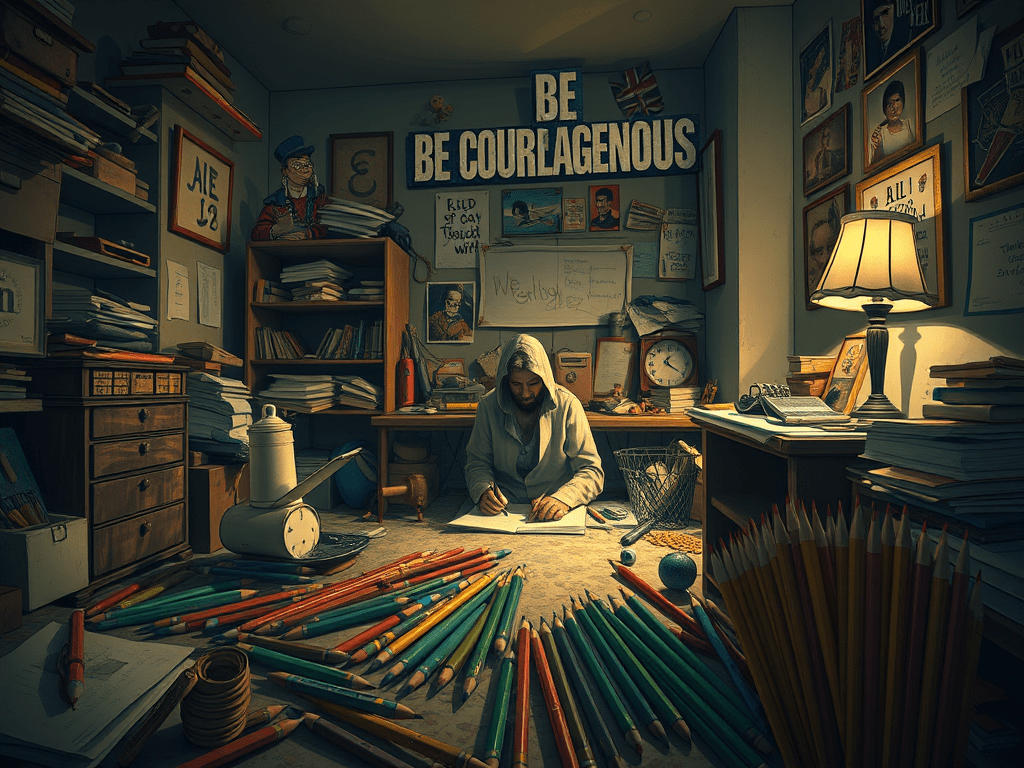

In the fall of 1979, I was seventeen years old, a freshman in college, and already trapped in the tragicomic theater of my own self-regard. My deltoids were large, my ego fragile, and my sense of fashion—catastrophic. I had shown up that day to the cafeteria in a tight black turtleneck, the kind of garment that might look sleek on a Parisian intellectual but looked positively deranged on a teenage bodybuilder seated alone under sun-drenched plate-glass windows. The sun baked through the glass like a punishment from Apollo himself, and there I sat, moping in a puddle of my own sweat and self-loathing while Jimmy Buffett’s “Margaritaville” chirped mockingly from the jukebox.

The song, a hymn to sloth and sangria, might as well have been composed to ridicule me personally. I didn’t know how to be carefree. I didn’t sip margaritas or laugh at spilled salt. I sat there glowering at my hamburger like it owed me money.

College wasn’t a choice; it was a parental ultimatum. My mother, newly divorced and perpetually exasperated, had threatened to eject me from the house if I didn’t enroll. My father, who fed me barbecued steak at his bachelor pad and treated my emotions like a disease he couldn’t contract, declared that my ego—his exact word—was too “delicate” for a job with the sanitation crew. “You’re not built for trash,” he said between bites. “You need a title.” I agreed. I said I needed something white-collar, something that sounded mobile—like it wore loafers and got invited to cocktail parties.

Yet there I sat, jobless, broke, sweating through a wool turtleneck like a fool in a Russian novel. Just a few weeks earlier, I had been juggling job offers like a hustler on the make. One gig was as a bouncer at a teenage disco called Maverick’s in San Ramon, a temple of polyester and hormonal chaos where high schoolers writhed to the anesthetizing thump of K.C. and the Sunshine Band. I hated everything about that job—the music, the fake glamour, the pretense of authority as I stalked the aisles flexing my lats like I was auditioning for a sequel to Saturday Night Fever: The Security Guard Chronicles.

My mother’s revolving door of boyfriends didn’t help. One, a Raiders defensive coordinator, had promised me a job moving pianos, which somehow never materialized. Another, Sid Briggs, was allegedly a “businessman” with Teamsters connections and the vague scent of federal indictment. He too promised me a job managing a health club. That never happened either. The only real employment I had was at Maverick’s, which came to a dramatic end during a riot. My fellow bouncer Martino and I decided we were too precious to die for three bucks an hour, so we walked out mid-melee and drove off down Crow Canyon Road. Martino repeated like a monk reciting scripture, “I’m not going to risk my life for three dollars an hour.”

We were fired. Unceremoniously. I was left with $300 in my checking account and a 1971 metallic brown Ford Galaxy that had just drained me dry with repairs. That car had the elegance of a Soviet tank and handled like one too.

And now here I was, sulking under the cruel sunlight, marinating in Buffet’s faux-Carribbean nihilism. “Wasting away,” he sang. No kidding.

At six feet tall and 210 pounds of resentful muscle, I radiated a kind of lonely menace. My professors were afraid of me. People steered clear. I was a human bug zapper. But then came John O’Brien.

He walked right up to my isolated table like he was planting a flag. Set down his tray, extended a hand, and introduced himself. A compact redhead from Boston with the kind of fast-twitch charisma that usually belongs to politicians or cult leaders. He had moxie, confidence, and a girlfriend who looked like a shampoo commercial. But unlike most people with that kind of glow, he wasn’t a narcissist. He had radar. And he picked up my signal loud and clear: lost kid, no job, no love life, no clue.

John decided to fix me.

First, he got me a job. He worked at Jackson’s Wine & Spirits in Berkeley and said, “They need a guy. You’re the guy.” He called me that night with the details. Two days later, I was on the floor learning about merlot and discount vodka.

Then, with the subtlety of a Vegas magician, he decided to address my romantic failure. He looked across the cafeteria, spotted two stunning nineteen-year-olds, and summoned them with a whistle so loud and precise it could’ve herded cattle. They glided over—one blonde, one with honey-colored hair—and I immediately began sweating like a man having a cardiac episode in church. It was flop sweat, and I couldn’t stop it. I tugged at the neck of my turtleneck like it was trying to strangle me and muttered, “It’s not hot in here.”

The girls smiled politely, and I squirmed in my own skin like a teenage werewolf caught mid-shift. John watched it all with the amused detachment of a man inspecting a fixer-upper. He had found a dilapidated house—me—and now he was assessing the structural damage.

He had his work cut out for him.