I’ve never trusted the mythology of self-help books—the fairy tale that you identify Problem X, buy a book, read a few hundred pages, and Problem X vanishes. What I do believe is that a self-help book, at best, can make you stare harder at your demon, dull its sharper edges, and maybe hand you a strategy or two to keep it from devouring you whole.

That’s why Anna Lembke’s Dopamine Nation: Finding Balance in the Age of Indulgence punched me in the gut. Her blunt lesson: dopamine addiction—whether through scrolling, swiping, shopping, or vaping—doesn’t lead to pleasure but to misery, pain, and the hollowing-out of your agency. Reading her, I shuddered at the years I wasted feeding my brain with Internet sugar highs.

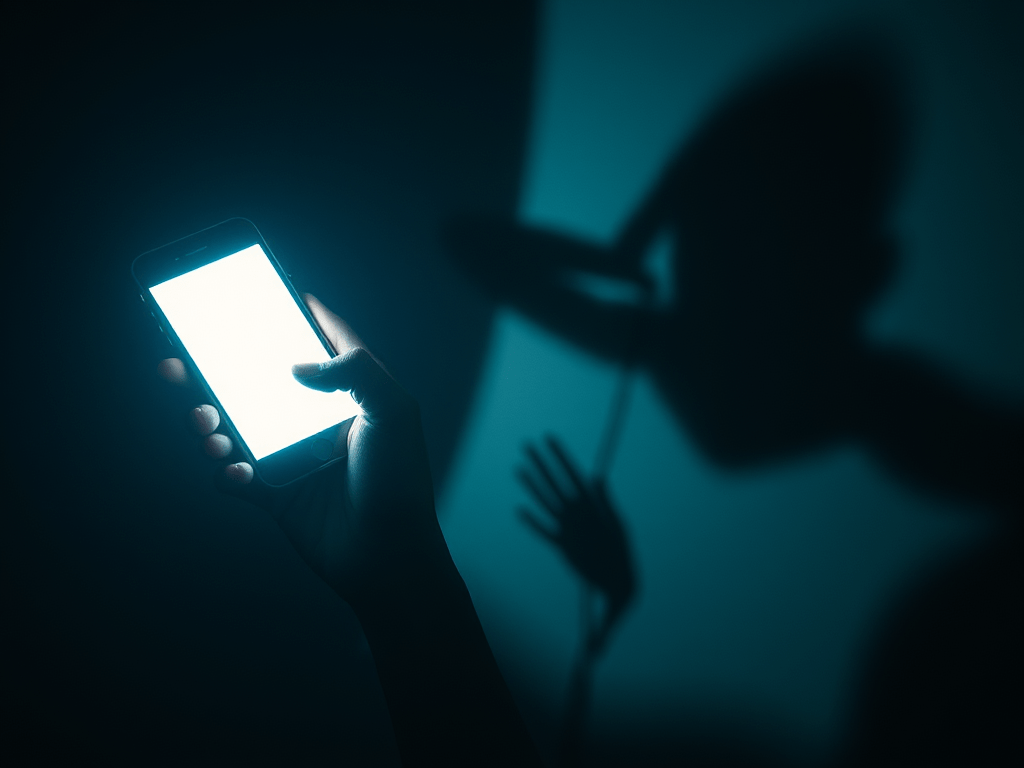

Lembke makes no bones about the world we live in: a digital carnival of “overwhelming abundance.” She puts it starkly: “The smartphone is the modern-day hypodermic needle, delivering digital dopamine 24/7 for a wired generation. If you haven’t met your drug of choice yet, it’s coming soon to a website near you.” Pleasure and pain, she reminds us, are processed in the same brain circuitry—and the more dopamine that flows, the stickier the addiction.

The horror story isn’t abstract. Her case studies peel the skin off addiction’s double life: secret compulsions, corrosive shame, shattered relationships. Some people are more vulnerable—those with addictive parents, those with mental illness in the family—but Lembke insists access is the true accelerant. The Internet puts a casino in our pocket; supply breeds demand. Worse, social media monetizes outrage until we mistake 24/7 hair-on-fire hysteria for “normal.”

Lembke’s most grotesque example is Jacob, a sex addict who literally builds himself a “Masturbation Machine.” She confesses she feels horror, compassion—and dread that she herself is not immune. Her verdict is bleak: “Not unlike Jacob, we are all at risk of titillating ourselves to death.” Seventy percent of global deaths, she notes, stem from modifiable behaviors like smoking, gluttony, and sloth. Addiction, in short, is a slow suicide dressed up as entertainment.

Part of the problem is philosophical. As Philip Rieff noted in The Triumph of the Therapeutic, “Religious man was born to be saved; psychological man is born to be pleased.” We’ve traded the pursuit of goodness for the pursuit of good feelings. Jeffrey Rosen put it more bluntly: classical wisdom insists we should aim to be good, not simply to feel good. Instead, we’re anesthetizing ourselves with meds, therapy-lite, dopamine drip-feeds, and hedonism. And as Lembke observes, hedonism curdles into its opposite: anhedonia, the inability to enjoy anything at all.

Her prescription? The brutal reset of a “dopamine fast.” Four weeks off your drug of choice to force your brain back to balance. She offers a framework—DOPAMINE (data, objectives, problems, abstinence, mindfulness, insight, next steps, experiment). It’s clever, but the hard truth runs underneath: most addicts, myself included, are not “moderators.” We’re all-or-nothing. For me, the Internet isn’t moderation-friendly; it’s a rabbit hole with no bottom.

Lembke knows willpower is not enough. She prescribes “self-binding”: physical, chronological, and categorical walls between you and your poison. But in the digital economy—where work and addiction ride on the same Internet rails—such barriers are fragile. Moderation may be the fantasy; abstinence the only real survival strategy.

So yes, I’m glad I read Dopamine Nation. It clarified the trap, exposed the double life, and framed the fight as both biological and spiritual. But let’s not be naïve. Like all self-help, it’s not a magic pill. At best, it’s a mirror, a warning flare, and a rough map out of the dopamine swamp. The walking out is still on you.

Leave a reply to g76921373 Cancel reply